Logo Image by Matt Fitt

Careful readers of this blog will be familiar, in a basic sense, with my political sensibilities. I am a critic of the current administration and the particular dynamics of the contemporary Republican Party. Hardly a secret, and for most academics in the humanities hardly a shocker either. The true conservative nature of the academy is rarely played out along such openly political lines, where it is quite possible to be both a "radical" and a rabid reactionary simultaneously. Now, this personal distaste for the Republican Party precedes our current administration by many years. I grew into political consciousness during the Reagan years, and saw first hand the deleterious effects of Republican policy in its milder, friendlier variant (the eighties, who knew?). My political sensibility was drawn both from immediate experience as well as moral and ethical compasses borrowed from family, teachers, and friends. I consider my politics to be, above all, humane: concerned with others, empathetic.

Mind you, as I meander along this pathway, that I have not described myself as a Democrat. I am, of course, registered as a Democrat, for what that’s worth. But, again, like many intellectuals, I have problems with the Democratic Party that stretch back to the Clinton years and the whole “don’t ask, don’t tell” debacle, among other things. But then again, I would be the first to admit leadership is hard, and leadership is what we have decidedly been lacking since, seemingly, Lyndon Baines Johnson, who I love as the expression of an American ideal in spite of all his well-noted flaws and errors.

What has led me to this brief, schematic political curriculum vitae is the current crisis over ABC’s telefilm, The Path to 9/11, airing this coming Sunday and Monday commercial-free to emphasise the gravitas of the moment. In short, ABC has produced a “docudrama” that claims to be based on the September 11th Investigatory Commission Report, but in fact deviates significantly from the report’s conclusions in a seemingly partisan effort to shift “blame” (if such a thing can be assigned in reference to 9/11) onto the Clinton administration. Those of you unfamiliar with the brewing scandal can read about it here and here, and take action here and here.

If this were just a kerkuffle on a Rightist blog, I would be less than interested, for after all, the American Right has had an unhealthy antipathy towards the Clintons in particular since well before Monicagate. However, the fact that a major television network is sponsoring this telefilm, written by a well-known conservative operator, I have found profoundly shocking and depressing, like the last vestige of hope for the Republic has slipped through one’s fingers. I know the ridiculousness of placing the hopes of the Republic on a commercial television network in the form of a doubtless incredibly cheesy and badly acted melodrama. But there was a time when networks attempted to avoid such partisan politics in favour of more vanilla moral messages. That time, apparently, has passed, gone the way of the loon along with the Fairness Doctrine.

Perhaps the first tremors of what was to come were actually contained in Gore v. Bush, our very own velvet putsch. But we continued on, angry perhaps, but not unnecessarily so. Americans, by and large, are a bland, conformist people. From such revolutionary and inspirational roots has grown a pragmatic and unimaginative mass culture. Our cities however, even the smaller ones, contain the vital life of the urbane, the striving, the questioning, the revolutionary in all its exalted and annoying aspects. To a certain extent this also exists, in a deformed version, in the universities. But out there, beyond the horizon of the cosmopolitan vision, lies a nation not necessarily scary as much as boring. It is not for nothing that the classic New Yorker cover showed a slim void where the heart of the nation lay, between the Hudson and California.

If you would permit me a moment of indulgence, Cold City is a remarkable example of this. In spite of the best efforts of banality, it has managed to hold onto some sense of the urbane, however strange a formation that may be. There is a small city centre, mid-density but full of people, apartment buildings, poorer and richer neighborhoods, parks, stores, alterna-youth, highways, boulevards, and streets, all very manageable and practical. Cold City is not terribly attractive, but it is serviceable. However, in the space of two generations, it has been put under the hot iron and spread, like melted butter, nilly willy in all directions. The sprawl is incredible, as first, second, and now third-tier suburbs ring the old city centre, connected by a freeway system designed for much less volume than must be dealt with today. There is, typically, no public transport system to speak of, and local efforts to revive streetcar service, which as was the case for many American cities was once extensive and efficient, have met with suburban complaints to the state legislature over monies diverted from “highway improvement.”

For me, personally, Cold City is a pale shadow of a city, amusing perhaps on the rare occasion, but largely invisible through a mutual ignorance. Cold City is not exactly friendly to newcomers, and my life has been so torn between here and there (Big Eastern City), that I have not found it within myself to get to like the place. At least there is sexual and racial diversity here, which I suppose is my way of saying it could in fact be worse, much worse. But for the regional transplants who have come from the dying Empty Quarter states and provinces, Cold City is paradise, where they can become who they want to be, free from the prying eyes of dying towns with no interstate exit. Chacun à son goût, evidently, which is to say that while I find the place dreary in the extreme (I am reminded of André Laurendeau's memory of gazing out of his Winnipeg hotel window onto an icy and snow covered parking lot: "What am I doing here?"), this is not without a recognition of the power of this urban(e) space for others, a blue-ish island in a red-ish sea.

Now, what does the space of the American city have to do with our partisan moment, one may wonder? In the space of half a century, Americans have jettisoned their cities for the suburban home, climate control, the SUV, and Big Box stores. What is lost is the quotidian contact essential to democracy: negotiation, consensus, and dialogue. Isolated by television and our vehicles and in point of fact our national misanthropy, we can fool ourselves into thinking we actually don’t need each other, or worse, that we don’t need the government. Without having to be uncomfortable, which in fact is what a true confrontation with diversity (of race, sexuality, opinion) is, we are marooned in a strange and frightening box where like-minded opinions reverberate like a horrifying echo chamber, slowly but surely driving us all insane. Perhaps we are already there, ready to retreat, like Lucía after her shoot out at Barajas in Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, back to the asylum, where it is more peaceful than the challenge of living in three dimensions. It is not an accident that North American cities have been under siege for the last fifty years, for cities are where one becomes polluted by the strange, the foreign, the different, the unknown, irrevocably contaminated by the race and sexuality white Americans have always been terrified of. City slickers, even the Cold City variety, have more in common with their brethren in cities around the world than with the country folks down the road, and as such form a cosmopolitan segment that rises above local, regional, and national politics, and therefore, also, containment.

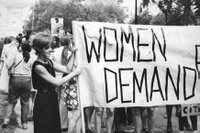

The legacy of 9/11, and what has followed, much more than what occurred before, reflect this procrustean bed of American nightmares, at the very least the nightmares of those who have forgotten what it means to connect, those who hate cities and what they stand for, and those who have hated or resented the social and political changes since the 1960s. The recently oft cited quote from Benjamin Franklin, “Those who would give up essential Liberty, to purchase a little temporary Safety, deserve neither Liberty nor Safety,” seems to ring especially true in the current moment. Perhaps our republican era has ended, and we have now moved onto becoming something else, something different: an Empire? An oligarchy? An autocracy? Who can be sure, in the middle of the metamorphosis? Committed Leftists would observe that we have been, at least since the end of the 19th century and perhaps before, all of these things already. And our current moment seems to share quite a lot with the Gilded Age, the darkness before the progressive dawn. Yet even in the Gilded Age, people were agitating for change, through labour organising or progressive and populist movements (however bad a reputation some of those might have), often times violent and dangerous work. The percolations of those movements are present, fleetingly, in our own age, but the ambivalence of the vast majority of Americans, on one hand, and the rabid partisan politics of smaller, better organised sectors of political society, have thrown a blanket over overtly expressive sentiments of Leftist or progressive or even (gasp!) liberal sentiment. The disabuse such rhetoric has fallen under is a function of many things, not the least of which has been dissension on the Left and zealous ressentiment on the Right.

I suspect, however, and as I have hinted at here and before, that the rightward turn of electoral politics and the never-ending march of the Culture Wars have their roots in irresolvable national questions of race and sexuality. If we trace the political through the cultural, a natural movement, we see the end of the liberal consensus at the same moment when the Civil Rights Movement began to make serious inroads into the infrastructure of white supremacy, at the same moment that sexual liberation, birth control, and safe and legal abortion (on a state, then national level) were beginning to significantly change (some would say modernise) American culture and society. The city, and the values of the city (cosmopolitanism, sexual sophistication, tolerance, negotiation) spreading its glorious wings over the nation, over the bland middle. And then all Hell broke loose. Oops.

A fact that I love to drop on my students, much to their dismay, is that formal white supremacy ends in this country in 1965, not 1865, with the passage of the Civil Rights (1964) and Voting Rights (1965) Acts by Congress. We are not that far out of the gate on this question, and the sustained attacks on racial justice (or even any question of racial justice) as well as the ever-present conundrum, seemingly, of contemporary LGBT rights, has rent the political fabric that, in its halcyon expression, was arguably grounded in white supremacy and a static social dynamic. And most distressingly, these attitudes have been sustained not (only) by the descendents of the English colonisers, but by and large by the white ethnic communities that arrived in the middle and end of the 19th century, who had a possessive investment in whiteness and its privileges. Where this race problem meets the problems of "deviant" sexuality of contemporary women and LGBT people is where we find the locus of the contemporary right centered around the Culture Wars. This pining for moral "seriousness" masks other, more disturbing socio-economic agendas that have marched forward as everyone dickers over whether gay people deserve to marry. The Pandora's Box of facing our changing and dynamic and ugly, resentful selves has been sprung, and there's no going back to either our pre-modern past of white supremacy and gender hierarchy or fantasies of liberal consensus predicated on rationality, especially given the incredible effort on the part of many to avoid looking in that mirror, the strange effect of which has been to deny that there is even an image to be reflected back.

All of which is to say that there seems to be little meeting ground around these questions, precisely because they are so foundational. White supremacy and the politics of resentment hurt us all, not just people of colour or LGBT people, evidenced most explicitly by the support some Americans express for a political party that does not have their, nor the nation’s, best interests at heart. I have written to ABC, I do my little work here and there to foment critique, but at a moment like the one we are living through, I am reminded of the 1978 march in honour of Harvey Milk, as related by Randy Shilts, the night he and the Mayor of San Francisco were murdered by a racist and homophobic white ex-policeman. As hundreds of LGBT and str8 people peacefully and placidly marched down Market Street, holding candles and crying, there was one real angry black queen, on the sidewalk, screaming at the numb passersby: “Where is your rage?!”

Where indeed?

1 comment:

Oso,

I love the original and assertive way you read these social symptoms. However, I'm a little surprised with your enthusiasm towards rage. Rage is not necessarily a positive force. Besides that, I must say I’m impressed by how you go across discourses, facts, mishaps, history, and pop culture to get straight to the bone of a problem (that otherwise would seem invisible).

In a way, you are like the character of "Interpreter of Maladies," a short story by Pulitzer- winner author Jumpa Lahiri. That good guy is a cicerone in India, who earns his bread with tourists lured by the exoticism of the ancient culture. His extra-income comes from a second work at a doctors' office, translating the “symptoms” of the patient to the “language” of the doctor. Because he is that link -- in the language, through the language--, there is hope and , possibly, a cure. Or not.

My point: you make visible constellations of symptoms that delineate sometimes known, sometimes unnamed diseases. Just like an interpreter of maladies. Important to identify constellations in this revisionist era where even Pluto was degraded.

Do you want to have breakfast in that non-planet?

Love your blog!

Cream Cheese (sorry for this cheesy nom de plum!)

Post a Comment