The beautiful baby boy pictured above is my Godson, El Babycito, the child of La Antropóloga and Mr. Polemic. He just had his first birthday, so the photo above is a bit out of date, however since I think all men look better with shorter hair, I am fond of this photo. I could swoon over his brilliance, his talent, his adorableness, but suffice it to say he is wonderful in his own special ways, as all children are before they discover the art of talking (back). Ah, the miserable joys to come!

The night La Antropóloga told us she was pregnant, Mr. Gordo and I had invited her over for supper, sans Mr. Polemic, who was elsewhere, exactly where I can’t remember. At the end of dinner, as we sat and yakked over the table, La Antropóloga announced she had something to tell us, to which I responded by saying jokingly, while blowing out a stream of smoke, “What, you’re pregnant?” When she answered in the affirmative, I was a little disconcerted, for a number of reasons. Mr. Gordo, of course, ever effusive, responded wonderfully. It took me a few weeks to regain my composure.

Why I would be less than excited by the coming of a child had a lot to do with how I consider(ed) parenting. Children are symbolic of so many complicated things: the end of adolescence, responsibility, maturity, adulthood. In one’s twenties and thirties, the carefree nature of adult life, the joys of adult life, and yes, the selfishness of adult life, struck me as the epitome of pleasure. Also, I could barely feed and clothe myself (some things never change). What would I do with a child? As I moved through this period of my life, I would often think of my mother at the same moment in time in her own life, for she had me at a young age. How she was able to accomplish parenting seemed like a divine mystery, a riddle of the Sphinx considered briefly as one applied cologne before going out to a fancy dinner with chums. It didn’t help that seemingly every heterosexual couple I knew at the time (and some LGBT ones as well) were getting pregnant or adopting babies or grabbing children off the street or however people go about getting children these days. It wasn’t that I didn’t approve of having children, I just didn’t want to lose my friends within the superstructure of modern parenthood, disappearing within the maze of obsequious "play dates", hypercompetitive endless yak about Junior’s progress, and precocious children interrupting adult conversations with mindless questions and demands. I feel/felt that parents in my particular intellectual and economic class experienced more than just the physical and biological changes that occurred during a natural human gestation: they also became in short order pod people, single-minded and decidedly unpleasant to be around.

Partially, this feeling was also reinforced by the phenomenon that was La Antropóloga and Mr. Polemic. La Antropóloga and I had begun working the same year at Sadistic College, and I remember our first meeting. I was at an introductory cocktail hosted by a very old but very jolly faculty couple (i.e. drunks) at their interestingly Preppy-Baroque-Scarsdale Killer home right before school started. La Antropóloga showed up with an old grad school chum, another young woman, in matching black outfits, and I just assumed, certainly from their physical countenance, that they were lovers. At the time, La Antropóloga had a tendency towards cute, ultra-sexy outfits that befitted her petite figure, a rare site among the majority of women academics I had known up to this point, who generally tended to match their male colleagues in a race to the bottom of the frump pile. In retrospect, the fact that she was so fashionable corresponded to my impression of La Antropóloga as a lesbian. At least in my universe, aside from their bad reputation, some of the most beautiful women in the world have been devotees of Sappho. Gimme a lipstick lesbian any day and twice on Sunday.

It was some time later that I met Mr. Polemic when he joined La Antropóloga in residence at Sadistic College, returned from whatever bushel his light had been hiding under, and then it all made sense, as one of those couples that seemed destined to find each other and belong, visually, aesthetically, and temperamentally, to one another. While I may have met him beforehand, the first lasting impression I have was at a party thrown at my small apartment, before Mr. Gordo and I lived together “officially.” Mr. Polemic ranged over a variety of topics, while drinking steadily. Charming, effusive, argumentative, and provocative all at the same time, he had the peculiar talent of nailing a point to the floor with a sledgehammer and a disarming, wry smile on his handsome face; all in all an unusual talent among academics, who especially amongst themselves tend to be as cautious and nervous as wallflowers at their first school dance. Together, they were bon vivants of a sort that I thought had gone extinct with smoking in airport lounges, the Gold Standard, Patricia Nixon chiffons, and gasoline at 75¢ a gallon, always impeccably dressed and groomed. I made the mistake once of showing up at their house for dinner at the end of one hot, humid summer day in shorts and a rank t-shirt, and had to suffer a delightful dinner astride them in their linen. Afterwards, recovering from my mortification, I always made sure to be put together for any little outing, whether that was the grocery store or dinner.

La Antropóloga and Mr. Polemic rapidly became a social centre of life at Sadistic College in those early, heady, and relatively happy days, and their parties became legendary, as much for the amount of top-shelf liquor and luscious, rich food that flowed from their kitchen as for the engaging talk and quirky, unstable personalities that surrounded their dinner table. It was like living in the fifties, where a drink (or three) before dinner was de rigueur and beef was always on the menu. So much so that Skanque Huore, always right on the money with witty impressions, began calling them the Kennedys of Sadistic College.

In this time, as well, Mr. Gordo and I had become quite close to them both, but the impending arrival of the proverbial bundle of joy, in my mind, brought the roof crashing down on the pleasant party we had been living. In place of cocktails, overflowing ashtrays, and huge cuts of grilled steak, various other cuts of roasted, fried, or barbecued animal flesh, and the other strange concoctions emanating from Mr. Polemic’s experimental kitchen, I imagined nappies, oversized prams, and macrobiotic, gluten-free snicky snacks. What a bore. By the time that La Antropóloga and Mr. Polemic asked Mr. Gordo and I to be the Godparents to the forthcoming El Babycito, I had resolved some of these questions in my mind. After all, what can one say? Don’t have the baby because then we won’t have as much fun? I suppose one could say that, but it doesn’t sound quite correct. But part of me was caught up in mourning the old relationship during the early part of La Antropóloga’s pregnancy, especially after smoking was, natürlich, banned from the house. In their defense, the soon-to-be parents were also conscious of the parenting trap that our society has elevated to a peculiar art, and vowed not to become pod people in that annoying Upper West/Dyke Slope sort of way.

When La Antropóloga and Mr. Polemic asked us to be the godparents of their El Babycito, we said yes immediately, incredibly flattered by the honour and privilege of the role. But like a true egghead, I began to ponder what it meant to be a godparent anyway. For a nominally Jewish couple and a couple of homosexual Catholics, what was the meaning of godparenting? Especially given the syncretic Latina/o Catholicism that Mr. Gordo and I practised, with our saints, candles, and fetishes, we certainly weren’t going to be escorting El Babycito to Confirmation in matching Brooks Brothers suits. We’d be lucky if we didn’t burst into flames at the Church door. So, doing what every egghead does now, I went to the Internet and researched godparenting, to help me answer some of my own questions regarding the practice, as well as be clear in my mind the nature of my relationship not only to my friends the new parents, but also to the baby. In other words, both Mr. Gordo and I took the role of godparenting seriously, and not as a somewhat outmoded social convention.

What I found online spoke to the rich history of Christianity as a spiritual practice, as well as the larger human dimensions of parenting beyond the nuclear family. Godparenting originally was related to the concept of religious sponsorship and training, for in the early years of the Common Era, when persecution of Christians was a regular occurrence, godparents ensured that the child was raised as a Christian if the parents should be unable to, either through death, disappearance, or dislocation, and/or to attest to the faith of the subject for entry into the faith.

After doing some of this initial research, I gathered one night with Skanque Huore and Mr. Gordo and we talked about godparenting and the role of LGBT people in the raising of children. If we, secular homosexual humanists, weren’t terribly interested in the actual Christian doctrine we were purportedly responsible for (which was already creaky, given that the parents were Jewish, we were homos, there is no godparenting tradition in Judaism, and none of us were truly interested in the dogmatic spiritual dimensions of the traditional role), then what exactly was our “official” role, especially since in the developed world even the Catholic godparenting tradition had become little more than ceremonious nothingness. So what exactly was it now? Gift-giving? Trips to Disneyland? The odd occasion of free child care? Mr. Gordo was more officially Catholic than I was, and actually had had godparents, including the head of a prominent Catholic family organisation in Venezuela who apparently provided fabulous gifts (a Fisher Price Airport playset!) until he ran off with his secretary in a naughty scandal. When Mr. Gordo told me this story, it reaffirmed my faith in Latin Catholicism.

My mother, on the other hand, had been so furious with the Church following her K-12 experience at the hands of taciturn and martially-minded nuns (“Penguins!” she would say dangerously, as she blew the smoke from her Virginia Slims 120 across the room and sipped her signature E & J screw top Burgundy on ice) that she refused to have me baptised at all, much to the consternation of my great-aunts, who began to dutifully bring me icons of saints and martyrs whenever they visited, as well as the occasional trip to church itself, although no one in my family was Catholic in the way the Roman Church imagines Catholicism, or rather I suppose in the way that Protestants imagine Catholicism. Like many US Latinas/os and Latin Americans, our relationship to faith was attenuated by indigenous practices: spells, magic, curanderas, offerings in the garden, the realm of nature, candles, icons divorced of dogmatic meaning but profound with power. And, of course, like any fabulous gay proto-Catholic boy, I had my own dreams of martyrdom and priesthood within and outside of these traditions and my mother’s dedicated secularism, delighting my grandmother with lurid Crayola portraits of the Crucifixion on craft paper, while at the same time she would nurture my fascination for lip-synching to Diana Ross’s Love Hangover into a microphone at six years old. In such tantalizing combinations Chicana/o experience can be found, strangely enough.

In any event, neither Mr. Gordo’s nor my own model of rather unconventional Catholic spirituality would quite do. As I turned to my computer, my online sources gestured towards the shifting potential of godparenting as a humanistic, secular practice. The night of our gallinero, Mr. Gordo, Skanque Huore, and I all agreed that this we could offer, not the faith as practised in our worst stereotypes of Catholicism (“Who made you? God! Where is God? Everywhere!” Et al), but the special faith of human and humane values that LGBT people can express and offer the world, and especially children. This is not to say that all LGBT people are somehow special, but rather to argue the point that LGBT people can offer something unique and vital to the raising of children, a perspective grounded in our location outside of heterosexuality, ideas about personhood, identity, and worldview that complement, enhance, and expand the idea of family in a positive way. It is to argue for the return of LGBT folks back into the “family,” not in a boring, mainstream way (although no doubt there are many boring, mainstream LGBT people doing just that), nor from a position of biological essentialism, but from the standpoint of our critique of heteronormativity and our rich tradition of synthetic familial relationships that emerge from our contemporary alienation from the biological family.

Of course, some would argue that LGBT people have never really left the family, that even in our varied states of alienation we are still present, even as unspoken shame, within our families. And, from what I’ve read, younger LGBT folks, at least from the bourgeoisie, may have more “normal” relationships to family that do not meet the classic pattern of dislocation and shock that typified “coming out” for many LGBT people (and still does). The nasty stereotypes about LGBT people, that we are infantile, immature, unrealized, can still exert a strong power over even enlightened parents on the role and relationship of LGBT people to their children. But what the odd progression of LGBT “liberation” and visibility means for us today is that LGBT people are returning to the family as both parents and members of extended families (such as godparenting), and for those of us to whom this matters, we are doing this on our own terms— not under the guise of bland asexual “uncles” and “aunts” but as ourselves: fabulous, idiosyncratic, and different. Such returns can offer their own riddle in a heteronormative culture, for sure.

I am reminded of my experience living with a faculty family whilst finishing my doctorate. I had returned from Montréal with no place to live, under intense pressure from the Dean to finish, and feeling alienated from California. With the help of my department administrative assistant, I found a billet with Chaucer Dad, a full professor in another department, his wife Philosopher Mom (also a PhD), and their two fraternal twin sons, living there for three years and completing the thesis under their roof with their incredible support. It was an interesting re-introduction to the family, not the least of which was that Chaucer Dad and Philosopher Mom were the exact biological age of my birth parents, the effect being that in the end I began to feel like the son from the first marriage, especially as we forged a familial relationship between ourselves within the house and formed a strange unit in public, with strangers attempting to figure out the dynamic between us (who exactly belonged to whom?). Chaucer Dad and Philosopher Mom had tried, through their feminist and progressive politics, to raise their sons with an eye towards a critique of gender and societal norms, which was successful in some instances and a complete failure in others, and much to the consternation of the other faculty families that surrounded them, who unsurprisingly were invested in relatively traditional orthodoxies of family. As I was to learn during this instructive time, theories of child-rearing and political exigencies wilt under the intense heat of actual children and their strange, secret cultures. When I arrived, the boys had just turned five, and they were wild, full of mischievous boy energy, a direct confrontation with a raw and untamed masculinity that had all of us perplexed and nervous.

They burned off the heads of the Barbie dolls they were given, and destroyed the purses and various feminine toys they had been given, while at the same time had been so exposed to LGBT people before my arrival that, at that time, they had no sense of LGBT alterity, in a literal sense. Once, when they asked me why I wasn’t married, I told them I guess I hadn’t found the right boy. They responded in their innocence and sense of care that they would marry me if I couldn’t find someone. I laughed and reassured them that I would indeed find someone my own age, as they would when the time came. But their response was so “normal” I was a bit disarmed. They had no “ick” factor, they had missed that lesson that boys marry girls and vice-versa exclusively and that any other option was “sick.” Sadly, their introduction to formal education and peer networks would shift this openness to human experience, this innocence about heteronormativity, and they became, in their early school years, a bit embarrassed by my presence, their strange “family,” the butt of a schoolboy joke, their very own “funny uncle.” This heteronormative homophobia induced by schooling was countered, however, by all that they knew about LGBT people and their relationships with LGBT people within and without the family. While the dimensions of this tension remain uncertain (they are now teenagers and as such are notoriously secretive about their feelings, especially as boys, a strange reassurance to nervous heterosexuals that even fabulous LGBT creatures parading through a childhood cannot prevent the tortured manifestations of teenaged masculinity), the existence of an alternative to the heteronormativity of the schoolhouse has at the very least forced them to articulate spatial and political dimensions with “normal” and carve out a recognition of different relationships within that concept, wherever that recognition may indeed be.

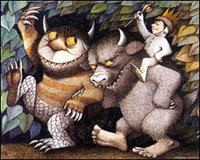

Surprisingly, Mr. Gordo and I share, as I find many gay men do, an odd affinity for children and their worlds, although I am perfectly willing to entertain that this may be exclusively a factor of being gordos and having facial hair, which makes us appear, especially to young children, like characters from Where the Wild Things Are, or alternatively, overly groomed stuffed animals, curious little hands tentatively touching beards, fat cheeks, bald pates, big hairy hands and arms. I am, however, cautious over the project of parenting, for that is what parenting is for most LGBT people: a project undertaken with great care and thoughtfulness, contra the majority of heterosexual births, which like immaculate conception, Mideastern political crises, and global warming, "just happen." As Camille Paglia once infamously quipped, “penis fits vagina.” Indeed.

In fact, within LGBT communities the question of parenting can be fraught with emotion, politics, and passionate disagreements. For every loving LGBT parent having children of their own or seeking to adopt here or abroad, you will find others who claim that not having children and the bourgeois accoutrements of the familial domestic is what being queer is all about. And while I appreciate and honour the labour of child rearing by LGBT parents (and for that matter, any parent really), I have had my own fears that our growing project of LGBT parenting may be reproducing the worst of our collective social narcissism in the spectre of the overly pampered bourgeois child, a risk most LGBT parents share with their heterosexual kith and kin. The ridiculously expensive prams, special diets, and child-centred nothingness that now parade shamelessly in plush LGBT urban neighborhoods are matched in the heterosexual world, and speaks to the general American obsession with unique and special children, every one a genius.

In any event, the arrival of El Babycito, the actual infant, transformed these theoretical paradigms of pre-birth discussion, worry, and conversation into a more tactile challenge. Here is a child. Of course, the changes for La Antropóloga and Mr. Polemic have been immense, but they remain, essentially, who they were before, if also now attentive to the needs of a growing child. Steak is still served, wine still flows, although unfortunately smoking remains outside chez eux (you win some, you lose some). For our part, Mr. Gordo and I have approached our relationship to El Babycito both in the effort to “take a vested interest in raising a more complete human being” as well as an integral part of our relationship to his parents, as a connection and bond and symbol of our love and deep affection for La Antropóloga and Mr. Polemic and the privilege of being a part of the raising and care of their child. For obviously in many ways it is a privilege, the same privilege we tend to take for granted as instructors in the classroom. Through our example, we affect the direction of our students’ lives. As El Babycito grows into boyhood and later manhood, Mr. Gordo and I can provide to him a complementary relationship, a parallel parenting in the best sense: of community, of difference, of sensibility, of connection. Teaching by example of the men we are: gay, Latino, intellectual, creative, loving, affectionate, bilingual, bicultural, introspective, not necessarily in that order. And gifts. Yes, of course, Mr. Gordo and I started on the gifts early, eyes full of extravagant Auntie Mame visions. But not Disneyland. Caracas, Curious George, Madrid, Tin Tin, London, the joys of department stores, the beneficial effects of high-end products, Paddington Bear, cute little outfits (and what age is cuter than toddler, I ask you? We introduced El Babycito to his first button-down onesie in blue plaid! Although the adventures of two large hairy gay men in the baby section can be enlightening to say the least…), literature, art, nature, even Teletubbies, yes, we are up for that. Mr. Gordo can sometimes act like a Teletubby around El Babycito, in fact. But Disneyland? That is decidedly someone else’s job. (Along with the nappies— In short, ew.)