This past week has been busy. Funny, but when I think of summer, I picture lolling about, late hot mornings with Venezuelan coffee and reading for pleasure and preparing bouquets of flowers and taking walks in the forest, waiting on Mr. Gordo to come home from work. At least, that was my summer vision when I lived in the country back at Sadistic College, playing a rather threadbare version of Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, except without a floppy hat. Here on my own until the end of June in Cold City, the end of the year and commencement of summer so far has been about work, not so intense as during the academic year but pressing enough to feel strange, a bit dislocating as the temperatures rise and the sultry humid air settles over our fair city. Wool gives way to linen, shoes to sandals, “moisturising” to “refreshing” body washes. The very space of experience is different as well: gone are the forests that surrounded our cottage with its babbling brook in the distance (literally), the wasp’s nest hanging in the tree, the deer in the backyard, the cardinal aloft from the branch.

Now in my little garret I see the side of the next apartment building over, which on some occasions offers interesting views, but only very rarely. More often than not all one can really see are the ragged urban squirrels click-clacking up and down the side of a very sad looking oak, with the urban soundtrack of distant sirens, and the roar of planes above, perhaps the rattle of bottles and cans falling into the recycling bin out back.

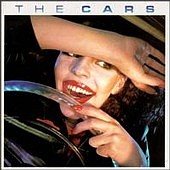

The one sensual pleasure that figures prominently is getting out of class at night and driving home along the interstate, the window down and radio loud, the lush air rolling over my face as I negotiate the freeway like a woman from a Cars album cover, all lascivious desire at the power of the engine, lighting a cigarette, changing lanes, sipping a Tab, and adjusting the volume on the IPod simultaneously. The immediate recovery of my pastoral bucolia is nigh impossible, for at the end of the session I shall be joining Mr. Gordo in hot, humid, ugly Big Eastern City (which, natch, he adores: his American dream) for a shared seven-week stint in a mid-size studio apartment on a loud boulevard, with pot smokers in the foyer and a pathetic air conditioner too small to adequately chill the space to my desired temperature of Nunavut. Let’s hope in this instance that Love indeed can conquer all. I guess another way to put it would be that some men are brave.

I am currently teaching a summer course with a lovely group of bright students who are invested in the topic and interested and talkative (!), in a beautiful modern classroom with a view of the skyline, which every session features the most amazing sunset to compliment our conversations. For the last few weeks I have also been participating in a faculty seminar on teaching, specifically concerning the question of difference in the classroom. When I went into this I was figuring, perhaps somewhat naively, that I would have little to learn. Very shortly I was disabused of this quaint notion, which perhaps even in its origin was too simplistic. In other words, I really should have known better, but sometimes I think the motto “Hope Springs Eternal” is tattooed on my forehead.

By this I mean that I always go into these things thinking the best of people, that my colleagues will be open and participatory and interested and invested in creating a learning community. Why I should persist in this thinking after my sentimental education at Sadistic College gives me pause: is this freshness of the ingénue tantalising in its possibilities or hopelessly pathetic? In any event, this optimistic approach is the millstone around my neck that I just cannot seem to shake, and it can at times be a real drag.

Now, any milieu that features discussions on the holy trinity of difference (race, gender, class) as well as a host of other conditions (sexuality, disability, religion) is sure to spark, um, strong feelings. Not the least of which is because these sorts of seminars have a somewhat bad reputation for being doctrinaire and simplistic, even among (or perhaps especially) the liberal faculty who take them. Our sessions are not mandatory, but participants do receive a small stipend for their participation, so there is a consensual element to the proceedings.

In any event, an incident in the seminar upset me greatly, and seemed to detail a number of problems not only with thinking through difference in our teaching but also difference among the professoriate. In short, the apex (or perhaps nadir) of our seminar sessions was a heated discussion of a recent racial controversy on campus. Many of the students involved in this controversy were actually enrolled in various classes of mine, and a number of them approached me: What should we do? How should we respond? How should we deal with our feelings of anger? (Although this wasn’t usually stated so eloquently, for more often my students wanted to literally go find the offending party and whup their ass: “We’re trying to find out where [offending party] lives.”)

As a faculty of colour, this is obviously not my first time in proximity to a campus racial controversy, nor the strong emotions that tend to accompany them, and I urged my students to craft, along with their feelings of anger and rage, an intellectual response to this conundrum. The reasons as to why I would respond thusly are manifold, and both personal and professional. One clearly is that physical violence has no place in a learning environment, which dovetails with my own experience with physical violence in my family, as well as the constant threat of heteronormative violence on the street and in public places. Violence, in my experience, comes looking for you, so why bother going out and finding it. Another is that emotional and rash reactions of this sort, as well as the pure emotive hair-pulling performed in invariably endless meetings, conforms to the vicious stereotypes of people of colour as incapable of intellectual and reasoned response. And this was a controversial moment that could support a pointed intellectual deconstruction (the campus controversy in question was grounded in a discursive racist moment, and was not physical, e.g. recent incidents at Duke).

Even as I say this, I realise from experience that while racist discursive moments may be dismissed as purely emotive (“Students of colour are upset”), they are also often simultaneously physical as well, in terms of students feeling threatened, or vulnerable, or feeling sick, or feeling angry. The point of my advice to my students (advice being key; they were of course free to follow or disregard my thoughts on the matter. Clever, yes, but Svengali I’m not) was to connect my students with their budding intellectual training at Cold City U: if white supremacy is a discursive system that manifests itself in both material and metaphysical ways and is moreover invisible as a system, how do we differentiate the level of risk in confronting it, as well as the level and intensity of response. In other words, how do we craft an intellectual response to the problem of white supremacy as ideology as well as through material action (literal resistance, struggle, protest, self-protection)?

The fact that this incident encapsulates many of the principles of the teaching seminar itself, principally how do we handle and accommodate different stakeholders in the classroom, would purportedly make this a perfect “teachable moment.” However, that was not they way it played out. Several white faculty were disturbed by my intellectual response to the campus controversy, and quickly moved to critique it (which of course was not the point of sharing it in the first place; I was not asking for their opinion). One of my immediate colleagues offered a professional critique that was well worded, immediately followed by an older white woman from another division who said, “Yeah, if I was your student and you said that to me [the need to develop an intellectual response], I would want to punch you in the face!”

Boom! All the conversation at this point was moving rapidly towards a false equivocation of my position as “mind” and others as “body/emotion” (which was not what I was saying), with many people chiming in and voices raised and the facilitator looking pained and trying to regain control, but after this last comment about a fist and my face, time stood still a bit for me. I was deeply shocked that a colleague would enunciate an advocacy of violence against another faculty member, much less one complicated by race and sexuality, solely on the basis of cultivating intellectualism in students of colour. Respecting difference, indeed!

Was it a poor choice on her part? Needless to say, yes, however, no apology has been forthcoming, and in fact, several other white faculty voiced their agreement with this woman’s statement at the moment (“Yeah!", “Exactly!”), in essence, saying that they believed in fact the correct response of students of colour to this campus controversy was violence, unbridled emotion, reaction, hysteria. Intellectualism was not, for these good white people, the appropriate response to this controversy. However, if the university is not the place for an intellectual response, then indeed where is that place?

We stopped for a break, before which one faculty member of colour astutely observed, “This is why it is hard to discuss race in the classroom.” I fled outside to smoke furiously and dial Mr. Gordo on the mobile. I returned, after a somewhat calming conversation, to fume for the rest of the session, and then spend the weekend processing this moment with my closest friends and professional interlocutors. I was unable to articulate my issues with this woman’s statement at the moment, to in effect "stop the process," as Prancilla would later observe.

In fact, through the many conversations we had regarding this incident, the one thing that stood out for me is that Miss Prancilla is one of the smartest people I know, as well as how lucky I am to have such interlocutors in my life. We dissected and analysed the moment, attempting to explain as to why, in a seminar devoted to teaching approaches to diversity, a moment like this might happen. Prancilla and I discussed and debated the symbolic value of the incident, which aside from the professional discourtesy of such a statement, had a lot happening that had little to do with me, personally, and much to do with the placement of faculty of colour in the academy (indeed, the violent rhetorical policing of the boundaries for faculty of colour), the debate over race and difference in an institutional context, and intra-institutional and disciplinary differences and struggles over institutional mission and direction, as well as a profound self-loathing contained in the anti-intellectualism of the response. In other words, what is it we are meant to be doing in the classroom for our students? Are we training thinkers or tending to issues of self-esteem? They are of course linked concepts but tend to be placed at opposite ends of the pedagogical spectrum. How do some faculty get construed as caregivers, why, and what happens when they fail to live up to this expectation?

Prancilla trenchantly observed that had I actually said to my students, “Yeah, go kick that white bitch’s ass,” that would have hardly been the subject of general approbation in the seminar. In fact, then one would have been molding themselves to fit into another stereotype, that of the violent person of colour. But in fact, this is what my white colleagues were implicitly advocating, including that I have my own face punched for daring to challenge students to think, not simply respond viscerally. It was the question of the punition of the professor I found most disturbing, and most compelling. What was at stake in this punishment? Was I being too smart for my own good? Was I being punished for being a professional? Was I being punished for being a bad “mentor”? As my old colleague La Antropóloga put it in an email to me regarding the seminar, “Did she think that by directing the students to think of an intellectual response you were undermining their anger/ passion? That they should be able to express their anger more clearly and directly (like by punching their professor in the face!! -- sounds all too familiar […]), and that an 'intellectual response' was not an effective form of response?” If indeed my white critics in the seminar believe that intellectualism is not an effective response, then what exactly are they doing in their classrooms? They didn't feel the need to share.

Prancilla advocated an intervention in the seminar to address this incident and my own feelings of anger regarding it, to demonstrate some of the profound problems that exist around questions of difference in the institution. I am personally not very receptive to open confrontation in person, but in the end the point was moot. Many in the seminar found the conversational moment awkward or tense, but could not remember the moment enough to articulate a critical position. One co-facilitator heard something different, another was aware of the moment, although was herself engaged in the conversation and unable to properly situate the moment. A Prancilla aphorism, a Prancillaism: “Either there’s something to what I’m saying, or I’m crazy. So if you don’t think I’m crazy, then there must be something to what I’m saying.” And this was the sense I had trying to measure the moment with other seminar participants. This happened, but seemingly was largely invisible to other witnesses, which itself was profoundly disturbing in that no one thought it odd or improper to advocate violence against another faculty member.

In any event, the possibility of a direct confrontation in the context of the seminar was lost when the woman faculty in question dropped out, due to “personal conflicts.” Ironic, and perhaps intentional, although I have no desire to pursue her with my rage, which at this point has largely dissipated to reflection and exhaustion. But maybe that is essential to the moment: faculty of colour have to deal with these situations every day (for example, my white critics did not serve as mentors to concerned and angry students of colour), and we are sensitive to the slights and instantaneous verbal productions that other faculty can walk away from, with the primary differential being one of labour: quite simply, we are responsible for a wide variety of work that our white colleagues do not have to do, both on the level of the symbolic as well as the literal. And frankly, that work is exhausting, never ending, and depressing in its regularity, in the expectation that such work will be present in our professional lives forever.

I have written about some of these questions before, but this incident drove me, in true egghead form, back to reading, to ideas, to the page. In particular, to an excellent analytical piece by Patricia Hill Collins called “Toward a New Vision: Race, Class, and Gender as Categories of Analysis and Connection.” Collins' work has been broadly influential in Ethnic Studies, American Studies, Cultural Studies, as well as other disciplinary areas in the humanities that concern themselves most clearly with race in the classroom, both as a topic and as a factor in classroom and institutional dynamics. She writes:

Whether we benefit from it or not, we all live within institutions that reproduce race, class, and gender oppression. Even if we never have any contact with members of other race, class, and gender groups, we all encounter images of these groups and are exposed to the symbolic meanings attached to those images. On this dimension of oppression, our individual biographies vary tremendously. As a result of our institutional and symbolic statuses, all of our choices become political acts (648).

Collins details the three levels of this politics of oppression: the Institutional, the Symbolic, and the Individual. The incident in the teaching seminar encapsulated the weight of this trinity in a nutshell, and the politics associated with the range of meanings therein. Debates within the profession between different disciplinary centres regarding the function of the classroom, especially around vulnerable populations (race, gender in certain fields, sexuality, etc), can be intensely symbolic, but also function on the level of the institution itself (in terms of mission) and the individual (in terms of the duties of individual faculty to these populations or discourses). The false dichotomy between body/emotion and mind is not only sustained by neo-conservative critics of the academy (with their call for standards, i.e. "mind"), but also ironically supported by liberal and radical teaching pedagogies that seek to teach the “whole” student (i.e. "body/emotion"), with the practical application of emotion in the classroom seeming, in the instance of my white faculty critic, to also contain problematic and troubling associations of emotion and race that favour the emotive over the intellectual in the name of empowering the student. In other words, as professors, are we responsible to/for our students’ emotive needs, as well as their intellectual ones? Is the classroom about self-esteem? How do we nurture “whole” people? Is that even our job?

We do not live in the jungle gym or the kindergarten (contrary to news from the hallowed halls of Congress). We are constrained in our quotidian lives by a number of rules that by both consensus and coercion we follow. I am a trained humanist with a doctorate, but I am not a psychotherapist. I see my role as guiding my students towards fundamentally intellectual patterns of thought and critique. I, for one, am not ashamed to call myself an intellectual, a thinker, someone who uses their brain, who by choice and training privileges, to a large extent, reason over emotion, even within the realm of the emotional (Mr. Gordo’s oft cited critique: “You’re intellectualising!”). At the end of our class time together, my students leave the room and walk back into the gloom of a deeply irrational and emotive society that loathes thinking and intellectualism and intellectuals. That mocks us and denigrates our contribution to society, that questions are credentials and our value. Our students arguably are up to their eyeballs in anti-intellectual sentiment. They certainly don’t need, in my opinion, that standpoint reified in the context of the classroom. Here, they might be able to achieve a state they cannot easily achieve elsewhere. If we don’t believe in the life of the mind, however defined, why are we here then at the university? To change society radically? A decidedly poor choice of venue, in my book, considering how rabidly conservative the Shop is.

This intellectual and pedagogical mission goes double for students of colour, who imbibe almost from birth their implicit unworthiness of intellectual endeavour in a white supremacist society, either through social and economic neglect or being read exclusively as a token if indeed they manage to climb the ladder into institutions of higher education. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t. If this incident in the teaching seminar was meant to chastise me for my method, it in fact reasserted the belief that what we need is more intellectualism, more thinking, more methodology, in approaching these complicated situations of the new academy filled with race, difference, tension. A simple retreat into the emotive is simply not enough, for we need to find a way to broach this divide between emotion and intellectualism in ways that honour the ability of students of colour to think critically and empathetically, within and beyond themselves, and have the confidence that they can do it. This goes for the symbolism of faculty of colour as well.

We are creatures of mimesis, we scholars of colour. We have learned the rules of the game, and play them brilliantly. As Collins remarks, “Our ability to survive in hostile settings has hinged on our ability to learn intricate details about the behavior and world view of the powerful and adjust our behavior accordingly” (651). Yet, as Prancilla noted in one of our late night conversations, perhaps sometimes we have learned these lessons too well. Do scholars and faculty of colour hide their anger, disappointment, and terror behind intellectualism? Do we use intellectualism to avoid hard political choices, even as Collins implies that all choices we make are political? Is this why so many faculty of colour feel deeply ambivalent over our talents, our success, our roles in the profession? How do we find our voice in this funhouse of distorted images? Is the "real me" the person who can (or cannot) confront this woman with my rage, my anger? Or is it rather the one who uses the written word, here, to respond? Are there other ways to resist? Or as Mr. Gordo put it to me, “Choose your battles. Is this a battle you wish to fight?” There are, there need to be, myriad ways to fight.

As I have said before, the work of difference within the academy and our society is hard, tendentious, difficult, arduous. It is not easy. There are no “safe spaces,” for anybody. We are all implicated, and must all work, on some level, to address these conundrums of difference, for they aren’t going away anytime soon. There will be no magical return to the days of Cordovans and twin sets in the university.

One of the reasons I admire the work of Patricia Hill Collins is that she is in fact a pointed critic who manages to rise above simple polemics. She recognises, on fundamental levels, the nature of the struggle we have set before us. She ends her article with a call for us to examine our positions (655). Like most good teachers, this is something I do all the time, as a matter of survival, both as the professor at the head of diverse classrooms as well as a professional academic. But this incident and the teaching seminar as a whole was a moment to reconsider, to craft my own intellectual responses grounded, ironically enough, in the emotive, in the shock of the profound differences between us in form, style, substance, and politics. In essence, to examine once again my own position(s). Academics of colour are constantly examining their positions, however I would only wish that some of our white colleagues, whether conservative or liberal or indeed radical, would do so with the frequency and urgency with which we approach this challenge.