As I have composed this series of entries on my undergraduate experience at Prestigious Eastern U, what seemed at the beginning as a simple narrative exposition has become something different. It has, in fact, been remarkably difficult to reconstruct a memoir that is both personally emotionally resonant and yet resists simple narcissism. I think this struggle with the word also represents, to a certain extent, the incredibly subjective nature of experience, and the challenge of communicating such subjectivity with an eye towards connecting the personal to the larger metasocial narratives of politics, identity, social and cultural formations, and the like. The left-feminist political truism of “the personal is political” might be easy shorthand for these desires of communication, these desires for connection, but putting the pieces together is actually in fact not as easy as the rhythm of a slogan, something that not only feminists of the eighties discovered to their peril but also we students and activists on the left when confronted with the complicated politics of similarities, differences, and the powerful force of identity politics of the time.

In the eighties, we weren’t terribly interested in the question of the weld, the problem of the connection, although we were forging new connections as we destroyed old ones. I remember one moment in particular, concerning my involvement with PU’s MEChA (El Movimiento Estudiantíl Chicano de Aztlán), the Chicano student organisation. In the spring of my freshman year, I met La Martina, an older undergrad returned from a year stint in Houston as a waiter/hustler, in the spring of my first year. I first saw him in the large undergraduate eatery, at the salad bar with a green sports coat, big hair, and a prominent pink triangle on his lapel. Like my clique, La Martin would be instrumental in teaching me about being Chicano and gay and intellectual and critical. His gay mentorship, his introduction of classic gay camp culture, including the use of “she,” his later touring with me of the gay Chicana/o bar and club scene back home in Los Angeles, gave me a language that was both sexualised, racialised, local (Los Angeles and the Chicana/o Southwest), and global (PU and the Anglo world). Together with him, several other locas (gay Chicanos), Chicana feminist women students, and under the aegis of a liberal and feminist assistant dean, MEChA was substantially changed through a gay and feminist velvet revolution that displaced the older, nationalist, and more heterosexist leadership pool. In the rush of our heady moment, a group of us “feminists and fags” marched to the campus post office and primary crossroads of student life that provided display space, in wooden, glass-fronted boxes mounted on the walls, for undergraduate organizations.

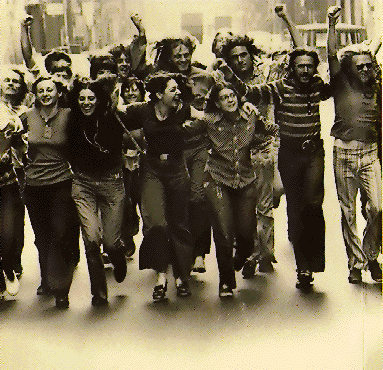

In an exhilarating moment, we opened the box and tore down the old, shop-worn cardboard display of Aztec gods and goddesses that graced MEChA’s organization display. At the time, such displays of sixties iconography struck us as embarrassingly retrograde. We considered ourselves young Chicana/o postmoderns, more concerned with anglophone music, fashion, and political values and struggles than with the myths and gods of a distant, heteronormative, and seemingly superfluous past. The fact that we never got around to recreating any sort of replacement that approached the archaic quality of the cardboard diorama of Aztec serpents we unceremoniously dumped into a trashcan was unimportant. The feeling at the time was that we were all actors in a play of great importance, a shift of thought. We were collectively involved in a feminist and gay rearticulation of the meanings of Chicanismo, a project that was not without its attendant campus critics, but one that we felt was ascendant. What is key here is the joy, the sheer pleasure of acting together, moving together, the pleasure of being one in a group of like-minded people, the power of the collective on the individual, and how the collective was composed of idiosyncratic individuals. That one was, in the end, not alone.

This example of MEChA and the feeling we had of being on the cusp of a zeitgeist carried over to other activities and the general student atmosphere at PU, whether debating politics in the local pizzerias or engaging in combat in other student organisations, meetings, dining hall arguments, classroom discussions. The personal became the political that then became the personal yet again, the endless cycle of criticism, debate, and contestation. My experience of education at PU, broadly understood, was thus largely extracurricular and social, I suppose like any traditional collegiate environment. I remember little of most of the classes I took, a handful of influential professors and TAs, my senior project advisor (whom I remain close to today), certain moments in classes, the dullness of Art History survey with its hours of memorising titles and genres, but the whirlwind of memories are focused around the personal, around what was happening outside of the classroom, in meetings and dining halls and dances and parties and trips to New York and Boston and DC and after my sophomore year, humid summers at PU, working minimally and drinking maximally.

Here the effect of the actual intellectual training is obscure, but forms a crucial foundation. For what was being said in this or that social or organisational moment was deeply influenced by debates raging in classes and among the faculty at the time, over post-structuralist theory, woman of colour feminism, “post-modernity,” the initial undergrad importation of Stuart Hall and the Birmingham School (whom I first read in a seminar called “The Decline of Britain”), the demand of PU undergrads to be accountable to their education, both in light of the elitist reputation of the place, as well as the competitive vigour of the undergrads in and out of the classroom. To wit, my career as an unreconstructed essentialist ended in a course on Black women's fiction, taught by an up and coming feminist professor who would go on to great fame in the nineties. Why this ended at that moment was the realisation of the gulf between theory and practise, between easy rhetorical solidarities and the hard realities of working to conceive the subject, the place of speaking, and where that rubber meets the road of differences, self-aggrandisements, delusion, ego and egomania.

What I learned at PU was the embricated and interconnected nature of my identity, as a person of colour, as a gay man, as a future professional from the working class, as a light-skinned person in a white supremacist society, as a consumer, as a poor person with an elite certification, as a person of colour with a white certification. I learned how to coherently take apart an argument, how to write, how to speak, how to intone, how to behave in a variety of social situations, which fork to use and what not to do. I mastered the art of subtlety, the art of flattery, the art of the attack. I learned the differences between “real” formal clothes and the off-the-rack numbers I had brought with me from California, I learned how to shop, how to appreciate a $300 pair of shoes, how to buy a shirt or tie, how to discern “class” from the perspective of the upper echelons, how to present an image of oneself that avoided or ameliorated questions. The key concept here would be the material power of representation, the “realness” of the queens of Paris is Burning: “Do they see me?"

I was educated in genteel racism and homophobia, about silent unpleasantness and discomforts, about the meanings of inside and outside, and how one could straddle, dangerously, both at the same time. I grew into several interchangeable skins, to be worn at will, to be displayed and performed when desired or necessary. I learned about power, in essence, and I had the initial inculcation into a practicum of caution surrounding a lot of these questions and challenges, the cold realisation that answers to complicated questions would not be found in sloganeering and the politics of reflex. Most of these things were perfected following my time there, but all were crucially informed by my experience at PU, if only for the fact that these identities were learned, taught in the particular milieu of the university at that place and time.

“I left home and became myself.”

Does this mean I wasn’t a person of colour, or gay, or what have you, before hand? No, of course not, although identity does change through life. For myself, the family provided a base to move away from, but could not alone or simply support the person I needed to become. Rather, it is to say that the particular and peculiar expressions that I give these articulations of self (racial, sexual, gendered, economic) are ones that, ironically, are largely grounded in the foundational narratives of myself as a young adult and student intellectual at PU. They are performative honoraria, even as they shift, grow, and transform, of a specific time and place and series of actors: The clique, La Martina, Big Sis, my senior project advisor, other friends like La Zeez and La Connaire, and the professors and the TAs and other undergrads and books and dances and articles and parties and ideas and experiences and memories and standpoints I would take with me into graduate school and subsequently the profession and my life inside and outside of academia. My own personal and experiential curriculum vitae that represents who and what I am.

To return to this series of moments in these posts has been emotionally draining, which I have found surprising. When I began them, last week, I was excited by the opportunity to revisit a complex and meaningful time in my life. Now, at the conclusion, I feel both exhausted with the effort of communication as well as feeling acutely the power of the limitations of the personal narrative as explicatory epistemology, although obviously one feeds the other. The danger of relying on experience as a teleological guide has been examined in some detail in the work of feminists (I am thinking here in particular of the work of Joan Scott), but it is one thing to read the theory and another to live it. This is the moment when I think we as academics, as intellectuals, have some trouble smoothing over the edges, resolving the contradictions, squaring the circle.

To take seriously the challenge of postmodernity, or late modernity, or perhaps just the messy historical, social, and economic moment we are living through, paraphrasing The Fierceness, is to embrace the abyss, the free fall of indeterminacy, which is a rather fancy way of saying that certainty is a luxury we not only can no longer afford, but more importantly is no longer available as a fantastical state of being. Certainty, however, is like a warm blanket on a cold morning: it promises comfort and reassurance and the smell of cinnamon and sugar wafting through the house. It is hard to live in reality (read the paper if you don’t believe me), but the alternative seems to be a comfortable place in a pot on the stove, the metaphor of the slowly cooking frog that has become almost de rigueur in the left blogosphere of late. The brilliance of The Matrix was to put these questions in an accessible pop form: Consciousness is hard, but is also a requirement for both adulthood and citizenship. As I peruse the silken pages of the alumni magazine now, I wonder about the role of consciousness in what could pass as the greatest moment of historical sleep walking in our nation’s history. When you are living, as the current undergrads at PU are, in the middle of a brocaded pillow, how is it possible to achieve some critical distance? There are, in classic intellectual style, no singular answers to this question, only more questions. For of course the consciousness of which I speak here is not a unitary state, but a series of fragments, passing views, pieces out of which we somehow craft a reality.

For this is certainly one thing I learned well at PU, even as (or perhaps because) the university itself was imbued in fantasy projections: things are quite often not as they seem, and excavating the self leads not to the singular omniscient subject but rather to a series of pathways and streams that are remarkable for the ways in which they are unconnected, random, divergent, and contradictory and par hasard. In short, I became, like Yellow Mary in Daughters of the Dust, "ruin't," in my case for the metanarratives of self. But better ruined than Stepford. For like Yellow Mary, I choose a certain freedom in exchange for certainty, and as we hear so often nowadays, "freedom ain't free," although in this instance this has a very different valence of meaning.

6 comments:

Yes, but Yellow Mary overcame her status as "ruin't" by returning home, rejoining her ancestors, and welcoming the next generation. Moreover, in the eyes of Nana (the stand-in for all those who came before us), Mary Peazant was never lost.

I am sad about the loss of the MEChA display.

Mexican artist Silvia Gruner has a video piece called "In situ." A pre-Columbian artifact (an original one) the size of an apple is placed in her mouth preventing her from talking. The video is a close up of the artist with this uncomfortable piece of her past in her mouth that filters everything she might say. Throughout the duration of the video she performs different reactions to this anti-natural intrusion that has been placed in her mouth: she licks it erotically and aggresively, she endures this absurd task, she gets bored of it, she chokes.

In a way, I read the disposal of the Mecha display as a revision of certain iconographies that have become a commodity, just another banal rendition of a more profound mythology that you or your classmates at PU probably ignored.

If you were giving that up and looking for a more "authentically" built identity (or the idea of an identity), I celebrate your post-modern ritual. It doesn't seem to me that Mecha members were being dismissive of the rich heritage Mexicans have to deal with but they were making up new traditions. Traditions should be refreshed and invented. Otherwise, the idea of continuity would be scarily conventional. And pessimistic.

Aztlan -like Atlantis, like Angria- is an imaginary place.

One more thing: Why do we Latinos celebrate May 5th as an expatriate Holiday? The Victory of the Mexicans over the French army in Puebla says little about the background of many other non-Mexican Latinos living in this country. I'm afraid that for the sake of unity we are sacrifying the complexities of our heterogeneity.

Thanks, "Yellow Mary," for your insightful writing, always inspiring and thought provoking.

What's wrong with simple narcissism?

Actually I find your writing dense and I have a very hard time following it. Maybe it's me.

Great series of posts, one of the best I've read. Was chatting about coming-out stories with a friend the other day - he mostly hates them for reificaiton of identity, I mostly like them for the fusing of the personal-political that usually accompanies them. I'm taken with the way you articulate how mobility and confidence comes with a class-specific price tag. How to hold that undoing close? I think such questions of subjectivity often lacking in the US academic blogosphere but they are important to the labour politics of the institutions, in a hard-to-define way. At least, these posts have convinced me of that a bit more.

I'm going to keep it simple: I'm moved by these posts, and they remind me of the ways that desire is so much a part of the way those marginal to the academy (poor, working class, first gen, glbt, poc) get embroiled in the fantasy structure of all it promises.

Post a Comment