The must-read thread of the moment can be found over at the fabulous University Diaries, where an engaged conversation is underway on Donald Kagan’s recent piece on Harvard, the collapse of core curricula, and the "Imperial Faculty." Kagan, ex-Dean of Yale College and Lady Huffenpuff Professor of Something or Other, uses the foibles of refining Harvard’s core curriculum, the scandale Summers, and Derek Bok’s recent work to indict what he portrays as the Imperial Faculty: a self-enclosed and hermetic world of eggheads and mandarins who have lost sight of teaching as a legitimate goal of university education, the potential effect of which is to threaten not only the quality of undergraduate education but the sanctity and social use-value of the university as a whole.

My first reaction to the thread at UD was positively allergic, as I think of Kagan as one of those endlessly angry conservative fuddy duddies, railing against women of colour, LGBT studies, and the changes in the profession engendered by the social movements of the sixties (such as affirmative action, diversity initiatives, curriculum redevelopment, canon debates, etc.). But, getting over the ick factor and in his defense, his article in the loathsome Commentary deserves some attention, only because he does skirt the edges of real debate in his piece, a debate that, in my experience, is too often dismissed out of hand, because of its bad reputation among the good people of the academy (that would be you and me).

As I pointed out over at UD, one of the most immediate limitations of Kagan’s argument is that it focuses on Harvard as a template for undergraduate education across the spectrum in ways that speak to Harvard’s “reputation” such as it were, but in fact puts too much emphasis on the effect of that particular institution across the spectrum of R1, R2, four-year liberal arts colleges, community colleges, and technical schools, the entire mixed bag of institutions and missions that constitute the contemporary North American educational apparatus. Harvard may indeed lead, but its effect becomes more diffuse the farther away (or down the pecking order) one gets.

That aside, the transformation of core curricula from traditional canonical knowledges to the admittedly hodge-podge collection of various tracks, sub-specialties, strange inferences, and institutional particularities we work within today, is used by Kagan as symbolic of the larger crises around education in our society, although he is also careful to cut such a circumspect path around this thorny issue that his piece offers no actual and upfront subjective diagnosis as to why this has happened, although it is implied in several places. He writes:

Does it matter that Harvard’s curriculum is a vacant vessel? It is no secret, after all, that to the Harvard faculty, undergraduate education is at best of secondary interest. What is laughingly called the Core Curriculum—precisely what Summers sought to repair—is distinguished by the absence of any core of studies generally required. In practice, moreover, a significant number of the courses in Harvard College are taught by graduate students, not as assistants to professors but in full control of the content. Although they are called “tutors,” evoking an image of learned Oxbridge dons passing on their wisdom one-on-one, what they are is a collection of inexperienced leaders of discussion or pseudo-discussion groups. The overwhelming majority of these young men and women, to whom is entrusted a good chunk of a typical undergraduate’s education, will never be considered good enough to belong to Harvard’s regular faculty.

Leaving aside the question of what makes up a Harvard faculty member (snips and snails and puppy dog tails, no doubt), the problems Kagan points to here are well known (do we sense a fatuous whiff of labour activism here as well, towards the exploitation of Harvard's doctoral candidates?), if lacking an immediate solution (which I suppose would fit discretely within his argument). Again, however, Kagan gestures here towards the fractious and pitched debates over the last forty years in the North American academy, but reaches for Bok both to contextualise the debate between the political forces of Left and Right in the academy as well as diagnose the problems of the university in its teaching mission (producing idiots, in essence). This summary of positions is nicely done, indicting Bok and other “leaders” for naming and addressing problems intellectually but refusing to offer true solutions for fear of raising the considerable ire of the "Imperial Faculty." He concludes with this dark proposition, saying:

This is not a battle over the control of academic turf. The turf itself is at stake. The twin purposes of a university are the transmission of learning and the free cultivation of ideas. Both are entrusted to the faculty, and both have been traduced at its hands. An imperial faculty that responds to well-founded complaints about the curriculum by, in Lewis’s words, “relaxing requirements so that students can do what they want to do,” thus leaving professors free to teach only what (and when) they feel like teaching and—though Lewis does not mention this—to select as colleagues only those who share their narrow political perspective, is no longer serving the purposes of higher education. It has instead become an agent of their degradation.

As things stand now, no president appears capable of taming the imperial faculty; almost none is willing to try; and no one else from inside the world of the universities or infected by its self-serving culture is likely to stand up and say “enough,” or to be followed by anyone if he does. Salvation, if it is to come at all, will have to come from without. (emphasis mine)

Oooooo, scary! Now, I agree, basically, with Kagan here on many points, oddly enough. Faculties have, in some cases, perhaps many, absconded on their responsibility to address the pressing questions of educational and social relevance that confront us. Yes, faculties, like government, the corporate world, and popular culture, can be cliquish and narrow-minded (shocker!). R1s tend to do a piss poor job of teaching, and that (related to Harvard or not), does have an effect that filters down through the profession. In other words, for many of us, teaching is the red-haired stepchild to research, especially for younger and probationary faculty, because that is where our bread is buttered, so to speak. And as I noted on UD, faculty generally work quite hard at their teaching. Just because pedagogy has such a poor reputation when it comes to tenure and promotion does not mean that the vast majority of faculty members in North America aren’t constantly thinking and revising and adjusting their teaching. This, as I’m sure you know, is hard work, and work we do constantly, generally without great reward or praise.

My intellectual beef with Kagan (aside from dismissing his snarky participation at the very end in Horowitzian Culture War positions) would be two-fold: firstly, to blame the collapse of core curricula (and subsequently, analytic and linguistic skill) on the faculty alone is a simplistic, sloppy error. The death of Core and the rise of consumerism has been driven by students, administrators, elected officials, and the general public as much if not more than the faculty themselves. Certain faculties may indeed be resistant to change and selfishly engaged in self-promotion and self-aggrandisement (Kagan’s case contra Harvard’s faculty struck me as about right, knowing what I know about Harvard). However, to generalise from Harvard’s faculty (of all places) to the rest of us is a pas jeté Kagan’s argument is incapable of making. It is pure Rightist polemic.

Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, the collapse of skills and Core are not one and the same thing. They indeed may parallel each other, in fact be intertwined in places, but they are distinct pathways of social change that are not inherently related. The end of mass-distributed and adequate baseline thinking skills is a widespread challenge many of us struggle with regardless of institution level, the roots are which are grounded in a number of social, cultural, and economic factors that have relatively little to do with the academy itself, and speak more to the crisis of mass education at the K-12 level that we as university educators inherit.

The passing along of such students through the system is one that the faculty, regrettably, does participate in, yes indeed, but I would argue we do so reluctantly and under considerable pressure from administrators, parents, and legislatures concerned with bottom-line statistics and not quality of instruction or demonstrable skills (Heard of RateMyProfessors? Hello!). All of which begs the question, is this skills building in the most basic sense even within the purview of university education? I would say decidedly no, however it is one that is now foisted upon us due the collapse of K-12 public education in this country, a collapse that has everything to do with greedy and selfish publics, racism and intolerance, classism and class hatred, and falsely populist elected representatives, and nothing with the Shop, per se.

So, let’s lay blame where it belongs, and not upon the easiest target, which of course is the realm of intellectuals, despised and resented in American society and therefore an easier mark than looking in the mirror. The new demand for university accountability, which on paper looks so compelling and rational, is of course one of the most dangerous aspects of the recent federal commission on higher education, which on some level seeks to replicate the disastrous federal policies towards K-12 on testing to (public) higher education. But such efforts stem from a socio-cultural myopia so extreme it borders on the pathological, and therefore need to be resisted with all our energy, even if it puts us in bed with elements of the Imperial Faculty (traveling and transitive, not exclusive to one institution or level, ultimately, but more akin to state of mind) that Kagan rightly indicts, for its shortsightedness and egocentric narcissism. Fiddling while Rome burns.

Lastly, Core (or core curricula) is really shorthand here for Canon, and the American canon is in crisis for a number of reasons that have to do with the changing perceptions of what constitutes knowledge. The reasons why we as a society would have moved away from “Shakespeare” (as symbol of Old Canon) for Toni Morrison (as symbol of New Canon) are complicated, nuanced, uneven yet widespread (and therefore shared). But the changes to the North American academy and the idea of intellectual educations, however controversial, are reflective of the larger questions confronting the multi-cultural, multi-racial, and polyglot white settler colonies of North American, and not sui generis within the academy itself. It is beyond the purview of this entry to account for those histories, however suffice it to say that to collapse the end of Core/canon with the end of skills and the crisis in teaching is a sleight of hand that tells us more about Kagan and the political drive behind his critique than the manifold crises we face, both as a profession and society.

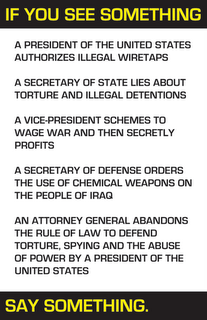

For, in the end, the Imperial Faculty must be, ipso facto, part of an Empire, and Kagan's implied populist solution to the crisis of education has all the hallmarks of a blatant, ham-fisted attempt to wrest control of whatever independence university faculties may have (however misused), and wed it to larger goals of Imperial control and surveillance, under the guise of accountability and the public good. Unfortunately, therefore, more of the same we've been getting for awhile now.

Poster by Laurie Arbeiter and Caroline Parker

4 comments:

This is a superb entry: its central point, that

the crisis over the canon of American universities

and the decline in basic skills of thinking, writing,

and the form of public speaking we do inside

the classroom are phenomena that must be

disentangled, is a brilliant step. So too is Oso Raro's

further claim that the failure to do so - indeed,

the wilful and unexamined conflation of the two -

suggests something that is more deeply flawed,

irresponsible and ultimately dangerous in Kagan's

argument. One additional point: it's interesting

to consider the difference between the contents

of any specific 'canon' or Core, on the one hand,

and the phenomenon of simply having a large part

of the college engaged in common texts and themes

at any given time.

This is a great post. Personally, I'm always offended by things like the snark against graduate instructors, most of whom are probably better teachers than many regular Harvard faculty, even if they will never be deemed "good enough" to join them. Bleah. In any case, I'll have to go check out the discussion at UD - thanks.

I get quite nervous when people start talking about a "Canon" because it almost always means 90% European/Euro-American, with a tiny sprinkling of people of color for zesty flavor.

Moreover, those disastrous k-12 policies you mentioned are a big part of the reason that universities are finding it hard to get students engaged with critical thinking. If you spent all of your education memorizing standardized answers, you aren't goi g to be ready to engage in an academic discussion.

What a wonderful, intelligent, precise post. Thank you for writing this.

Post a Comment