The benefits of two thousand years of Western civilization are familiar enough: an extraordinary increase in wealth, in food supply, in scientific knowledge, in the availability of consumer goods, in physical security, in life expectancy and economic opportunity. What is perhaps less apparent, and more perplexing, is that these impressive material advances have coincided with a phenomenon left unmentioned […]: a rise in the levels of status anxiety among ordinary Western citizens, by which is meant a rise in levels of concern about importance, achievement, and income. A sharp decline in actual deprivation may, paradoxically, have been accompanied by an ongoing and even escalating sense or fear of deprivation. Blessed with riches and possibilities far beyond anything imagined by ancestors who tilled the unpredictable soil of medieval Europe, modern populations have nonetheless shown a remarkable capacity to feel that neither who they are nor what they have is quite enough (25).

— Alain de Botton

Today dawned hot and humid in Big Eastern City (BEC), purportedly the latest hottest day of the year, after yesterday, which indeed was the hottest day of the year. As of this writing at 8:11 am, it is 83 degrees Fahrenheit with a Humidex of 86 degrees, and rising. A quick check of Cold City weather shows that indeed it is colder, at a relatively chilly 68 degrees. I am in the middle of my third week here and activities, like the weather, have been desultorily busy, yet strangely ritualistic as well. I have given up to the weather and have been staying in during the daytime while attempting to manage the secondhand smoke in Mr. Gordo’s Easy Bake Oven of an apartment. I read novels. I watch Oprah, who finally caught up to Bitch PhD on bra sizing yesterday. The Voice came through town last week on a three-hour tour of BEC, staying a couple of nights with us, we shopped until we dropped, and had a lovely dinner with Big Sis at her perennial favourite restaurant, after much hemming and hawing and annoying plan making. As Mr. Gordo’s sassy artist neighbor puts it, these are the days when you return home and want to burn your clothes.

Mr. Gordo’s Easy Bake is located in the heart of one of the most famous black neighborhoods in BEC, one of the great Eastern centres of Black diasporic culture. Like most historically Black urban neighborhoods, it is undergoing massive changes in its ecosystem, with an influx of new Latino immigrants, “hip” and/or economically-minded whites, property speculation, the long-term social changes triggered by desegregation (the flight of the Black middle classes, the rise of intractable institutionalised urban poverty) and the dynamic of incremental yet seemingly inevitable gentrification. And then there are the folks in Mr. Gordo’s building, an idiosyncratic mix of multi-racial professionals (artists, musicians, creative types), hispanophone immigrants, and drug dealers. It is not exactly Women of Brewster Place, but is more akin to The Street. Because of its famous reputation, this barrio has a politicised racial identity different from other Black and Latina/o neighborhoods I have lived in here in BEC, and the racial tensions on the street are palpable, and mostly unpleasant. The sexual ramifications seem more distant, and Mr. Gordo and I are regularly mistaken for brothers (displacement of identification?), which has come as a shock to both of us, since I feel we look nothing alike. Instead of trying to explain our real relationship, we have given in to saying, “Yes, we are brothers,” while we keep briskly walking. This is not the first time we have had a case of Dead Ringer: an old BEC landlady would regularly confuse us, to the point where I started answering to Mr. Gordo and he to Oso Raro in conversations with her. It was just easier. Sure, we are both gordos, and bearded, and have bellies, and wear glasses, but that is where the similarities end, for me at least. Self-perception, however, can be quite different from how one is perceived. Our theory is that others can “see” our intimacy, and instead of doing the math (“Oh, they’re lovers” or whatever), come up with a sanitized, easy answer. Maybe they’re asking something else of us.

Mr. Gordo (and I, by extension) has been on an existential trip, reevaluating everything from employment to domicile. And while indeed Mr. Gordo’s Easy Bake may indeed be in a bad but gentrifying neighborhood, the kind of neighborhood that you need to have a game face on when you walk the streets, the space itself reflects to a certain extent a personal stasis that has nothing to do with the barrio. Firstly, the strange echoes of our old house ring through the space, as most of the furniture was inherited and brought down from the country, where it once looked cute and pristine paired against the 19th century wide plank hard wood floors and doll house features of a worker’s cottage. Here in a large and fairly square BEC studio, with sirens outside and noise and traffic, there is a big space in the middle of the room that begs a tango class, with the furniture against the walls. Everything seems out of proportion. The bed is on the floor. The place looks like it did when Mr. Gordo moved in last summer, as if he is still unpacking, which I suppose in a sense he is. All it needs is a Van Halen poster on the wall and its transformation into a dorm room would be complete.

Secondly, as I realised last night while scrubbing the stove dripping sweat in the post-midnight heat, Mr. Gordo is also just a plain old-fashioned slob. Yea, the neighborhood might suck, there might be (relatively friendly) drug dealers lined in front of the building like a July 4th picnic, on folding chairs (!), but that’s no excuse for slovenly domestic habits. Cleanliness is next to Godliness, as they say, and like any good Latina daughter, this boy knows how to clean a house to get closer yet to the Virgin and various santos. Mr. Gordo knows how to clean as well, but it was clear from the stove that he has not necessarily been utilising that talent for the past few months. (This is why we employed a housekeeper when we lived together.) Does that mean he is (more) sinful? Or just a slob? Or just a man? Or all of the above? I’m not confident enough to venture an opinion, but suffice it to say I have been playing Cathy Cleaning since I arrived. My personal algebra has figured that an outlay of $1000 would easily turn Easy Bake into a showplace, but for the time being (not having a spare $1000 burning a hole in our pockets) we have made more economical improvements, like installing hooks and different light bulbs and the purchase of a real ashtray.

I suppose like many academics, I am incredibly sensitive to domestic spaces, partially because I have moved house so often since leaving my mother’s house back when I was a young lass. All might be chaos and swirling light, but if one’s home is propre and organized then one has a moment of stillness in the sturm-und-drang that is the academic life. All of which is one of the reasons as to why the lack of development in the domestic space chez M. Gordo has been both an immediate challenge (making the space more livable) as well as emotionally daunting. There is an element in our relationship that switches and changes depending on situation, where Mr. Gordo and I alternately play the practical guy to each other’s personal follies. I feel I definitely play that role in the realm of the household, and Mr. Gordo tends towards this position in terms of my management of personal, ahem, finances.

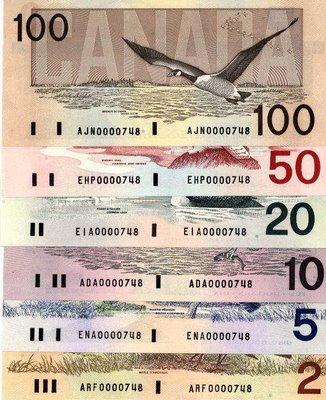

And it is to money that many of our conversations have turned these past weeks. Where is it? Where did it go? Will it come back? How to get it? How to get more? For again, here, the domestic is symbolic: Mr. Gordo’s neighborhood reinforces and undermines suspicions about one’s class standing in ways that are awkward and uncomfortable. I grew up in a similar neighborhood, a mix of poor and lower middle-class people, struggling to a certain extent with quotidian survival, living paycheck to paycheck, and to return to this origin point in such a literal, physical way has not been joyful. The human misery just outside of the window has some days been too much to bear, in response to which I no longer look out the window so much. Urban nomads, drugs, homelessness, despair, the urban schlepping, the tatty overpriced ramshackle stores and filthy dust-covered bodegas reminds me just a bit too much of where I am from, for which I am not ashamed but also do not romaticise. It is not cool to be poor in this country, and it certainly is not bohemian to live in urban zones of disempowerment and poor city services. It is, frankly, mostly uncomfortable. At 22, one can fool one’s self into thinking that such living is avant grade, or grown up, or temporary. At the end of one’s thirties, that is a harder tune to hum.

I know that one of the tropes of Mr. Gordo’s existential mood has been the neighborhood, the way its failure seemingly speaks to a more personal, subjective cul-de-sac. This is of course the function of these spaces, and they work extremely well, to invisibly reinforce the brutal class politics of our society as well as render meaningful opposition neutral. Now, I could point to some salient facts: that the cost of living in BEC is very expensive; that Mr. Gordo’s domestic problems with location and street life (crime, disorder, ugliness) are in fact rather quotidian troubles in BEC (Welcome to BEC! You’re miserable and want to move, like everybody else!); that the neighborhood itself, certainly compared to ten years ago, is in fact much better (crack has given way to marijuana; the Meth labs seem to be someplace else); that the apartment itself is a steal (big, light, airy, very cheap by BEC standards), and that the quotidian discomfort of having to run a gauntlet between young and intimidating black market economists and entrepreneurs on the street is a small price to pay in BEC to be able to get out of bed and not bump into your dresser or fall into the toilet.

But these realities don’t stand a chance against the amazing luxuries that BEC rubs in your face every day (homes, objects, fashion, restaurants, “lifestyles”), in addition to the personal measurements and evaluations of ourselves on a class scale. After all, Mr. Gordo and I are almost forty years old (we were born six weeks apart), a little long in the tooth for That Girl! fantasies of husband-hunting and Mary Tyler Moore “making it on our own” class dynamics. We are professionals, with degrees and a certain standing in our different work environments, and yet find ourselves still struggling to achieve bourgeois respectability in a solid, tangible way, which actually in this case means having cash money.

And this is what it is about, in many ways. What does it mean to have financial wherewithal, freedom to live in the manner one expects (wants), to have financial security? How do these relatively modest (at least in our case; we don’t want the Taj Mahal, just someplace pleasant, as loaded as that term may be) expectations meet both self-imagination (where we should be) as well as social and economic expectations (both legitimate and fantastical)? For we live in a society deeply malformed by the strange and curious invisible class structure that largely determines our lives. It is a truism that Americans don’t think about class, that we are a classless society, that anybody can make it here, that opportunity is just around the corner, that if we work hard we will prosper. Simultaneously, the failure of these bedtime stories composes a compelling (if somewhat played out) melody in American popular culture. One could argue that these ideas are grounded in an American optimism, a belief, however naïve or lunatic, in bright futures, happy endings, possibilities. In point of fact, Americans are constantly thinking about class, as obsessively as we think about our other, more public bugaboo, race, and how the two become linked both historically and in the contemporary moment is an exploration of the dark, nihilistic depths of the American soul.

Last week, in a reading jag brought on by events outside the window, I consumed in two days two autobiographical explorations of Californian upper class life: Joan Didion’s Where I Was From and Sean Wilsey’s Oh, the Glory of it All. Didion’s work is a reflection on the changes and transformations in Californian life from Anglo settlement in the 19th century to the post-war influx of other white Americans that changed and destabilised these older notions of Californian identity. Wilsey’s nasty tell-all focuses on the rich bitches of contemporary San Francisco society, especially the seemingly evil stepmother figure of Dede Wilsey, which, in comparison to Didion, is a rather sophomoric version of the "poor little rich boy" story. Curiously, both relied on the history of the conquest of and movement to the West in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (the Myth of the West) to examine how contemporary Californian life became structured, distorted, damaged. This was an interesting connection to me, in so much as we don’t think about those things in relation to class and class expectation: as a society we treasure the tabula rasa, the fresh start. Didion and Wilsey imply that the older, hidden narratives of where we’re from guide our lives like an invisible, deep ocean current.

This point seems obvious to those of us who, because of our intellectual capacity and our different (poorer) class origins relative to our current status through education, are hyperconscious of class and class symbolism. But for many Americans, who do not question our capitalist "running of the bulls," with winners and losers as a natural state of being, such lines of thinking are not productive, drag down too much on the fantasy of Horatio Alger, are too depressing to realise. The house of economic cards we live in continues its rapacious growth, through credit, debt, equity, consumerism, fashion, and lottery tickets, even as the cosmic cash machine that is the American class dynamic starts to bare its fangs in a more aggressive way. It has been a long time since Americans felt the true cost of capitalism on a wide scale in the form of a real nationwide economic crisis, and the potentials and dangers of such moments are, historically, what has kept American democracy alive, in the face of plutocratic greed. Like Hegel’s teleology, American society has typically reached impasses and developed upwards, resolved contradictions, synthesised conflicts. But this does not mean the Hegelian dialectic is the natural state of things, for in each of these conflicts the possibility of real peril, socio-economic or oligarchic, was always close at hand (the Progressive Era at the end of the 19th century and the Great Depression are the two most salient examples in this regard). We seem to be reaching another of these historical carbuncles: will the infection burst and heal, or spread dangerously inwards? The resolution (Butler’s Parable of the Sower or a newer New Deal) is still unknown. Before the events of 2000 (our velvet coup d’état) and 2001 (terrorism as a domestic political tool), I would have displayed more confidence in the ability of the American Republic to rebound and thrive, but now I am unsure, dismayed, disgusted, afraid and nervous and agitated.

While awaiting the coming crisis (the image of the Left, drumming its fingers, waiting for the perpetual crisis, is in my mind here), in hot, humid, rich and squalid BEC, my mind has turned, naturally, to the more personal choices one makes, sometimes unknowingly, that determine one’s future(s). When I graduated from Prestigious Eastern U., I lived for the year afterwards with three other PU graduates in a railroad flat in San Francisco, where we argued bitterly, had some fun, and grew up a bit. We have all gone on to become relatively accomplished in our various fields of medicine, law, writing, and academia. But the assumptions of equality and ambition present fifteen years ago have given way to other, less pretty realities, which speak to both the fantasy of PU as a place as well as the foreshadowing of choice. I have been focused on one of my old roommates (who I haven’t talked to since I decamped in his apartment for a night coming back from Europe in 1998, en route the next day to Montréal), who after taking his BA in English at PU, went on to über-prestigious PU Law School, joined a firm in BEC, and in short order was named partner. I once visited him at his office downtown for lunch, many years ago when we were still close: a big black steel ziggurat of Mammon with a Brooks Brothers in the lobby and remarkable views from the lobby of the forty-fifth floor. I can’t remember what we discussed, or what we ate for lunch, but I do remember the tower, the repressed mannerism common to all corporate spaces, and the view. I don’t remember being particularly impressed, but this was a long time ago.

We fell out of touch, primarily because a) I lived in California and he was in BEC, and b) increasingly we had relatively little in common (What exactly is the connection between a humanities grad student and a corporate lawyer?), although for several years he was one of the few people to remember my birthday with a card. I rang his office a couple of years ago, on a lark (his home number was unlisted), and left a message that was never returned. But a Google search reveals that he is doing rather well, on the boards of several charitable organisations, vacations on Fire Island, is an art collector, and in an interesting story in the BEC newspaper last fall, is looking, with his gold digger boyfriend from college (a complete but pretty idiot then and now; the article quotes him extensively and lists him as a major cable network “producer,” although his name is not to be found on their website nor via Google, aside from his seemingly superfluous doctorate from Harvard), for a house in a newly fashionable rural area north of BEC, to compliment their fashionable downtown loft and their fashionable Fire Island share and, no doubt, their fashionable art collection. This old roommate was, at the time, unassuming, cute in a strange, nerdy way (I had a big crush on him when we lived together), and came from a striving Italian American family in Connecticut that didn’t waste time on the intellectual fantasies that some of us associated with PU. Unlike myself, old roommate did not confuse college with the terminal point of success, but as a step in the right (capitalist) direction. How did he know this? Superior secondary school training, a better sense of the world, grasping parents driven by capital and acquisition are some easy reasons. Suburban Connecticut, with its cut throat class dynamic, is also a suspect here. The ability to game the system depends on knowing the system. I, and others, would only know the system after some years struggling within it.

A Google image search revealed his corporate photo, which met every stereotype of the soul-sucking nature of corporate work. I mean, none of us is twenty and fresh anymore, but some of us have managed to still look relatively human. I sent the picture to another old roommate from that year in San Francisco, Mrs. Dash, who practised law for a few years before moving on to writing full-time. She wrote back, “[…] it's funny, when I first started practicing law I would look at the photos of the partners and wonder what it's like in the empty shell where their souls would be […] and now I look at that unfortunate photo of dear [old roommate] and I still wonder the same thing.”

What does this tale tell us about class? That Mammon demands his pound of flesh? That those of us who have chosen more modest financial rewards for freedom of conscience look better? That those of us who did not make the proverbial Faustian bargain have retained something more than the physical outer shell of ourselves? All of which may be true, but in this city of desire and inequity and need and desperation and grifters, who wouldn’t desire a bit of that Faustian bargain? The example of the old roommate begs again the question of choices, of desires, of pathways.

My Big Sis claims I am too focused on the old roommate. In a long post-midnight telephone conversation that ironically we only seem to have anymore when we are in the same city, he pronounced that I am a thousand times richer, intellectually et cetera, than old roommate with his ready cash and lovely, comfortable downtown loft sans drug dealers (unless, of course, they are invited). This is true, but is also something of a cold comfort, in the end.

While ranging across the city with The Voice, we came across a little bookstore where we paused, sweating (the ubiquitous sweating) to browse the tables outside. The Voice picked up a book on ladies in pants, while I bought a copy of Papillon and a smart little book by Alain de Botton called Status Anxiety. It seemed apropos to the current moment, and reading it has been instructive, both in its examination of how the poor became horrible and the rich honourable (not the way it always was, and an interesting example of Nietzsche’s dictums), but also how the elevation of accumulation has triggered critical responses in various arts that seek to displace or recentre status away from Mammon towards other, more humanistic ends (the section on comedy and satire, the critique of Napoleon and 18th century society in England and France, is very funny; his reading of Madame Bovary and tragedy had me running out to get a copy to reread). De Botton writes in his pithy conclusion:

Status anxiety may be defined as problematic only insofar as it is inspired by values that we uphold because we are terrified and preternaturally obedient; because we have been anaesthetized into believing they are natural, perhaps even God-given; because those around us are in thrall to them; or because we have grown too imaginatively timid to conceive of alternatives. Philosophy, art, politics, religion and bohemia have never sought to do away entirely with the status hierarchy; they have attempted, rather, to institute new kinds of hierarchies based on sets of values unrecognised by, and critical of, those of the majority. […] In doing so, they have helped to lend legitimacy to those who, in every generation, maybe unable or unwilling to comply dutifully with the dominant notions of high status, but who may yet deserve to be categorised under something other than the brutal epithet of “loser” or “nobody.” They have provided us with persuasive and consoling reminders that there is more than one way— and more than just the judge’s and pharmacist’s way— of succeeding at life (293).

Here de Botton reifies everything most professors and intellectuals feel about themselves, on some level: that we inherit a rich tradition of critique and resistance, that we think and feel in different ways from the majority of people, that we embody a critical sensibility. Some of which is no doubt true about some academics some of the time. It is our masochistic reward for being paid and treated shabbily by a culture that demands accountability but refuses to pay for it in one of the most crucial social fields: education. In the world of Mammon, educators get short shrift (the social truism of “those who can, do— those that can’t, teach” rings through here). Academics never tire of stories of others impinging upon our professional territory, offering solutions and unasked for advice at the drop of a hat. This is because education, like parenting, seems so familiar to most of us, even if we do not understand the ramifications of the actual practice. In this regard, everyone seems to be an expert, although those of us who actually work in the field know this to be a disastrously untrue notion. Following de Botton, however, modesty and caution are no longer social virtues.

While indeed we may inherit the tradition of resistance to Capital status in the modern age (I certainly think of myself here), we live in a brutalist society where the consequence of the decision to become an academic is, for most of us, a reduced financial capacity. While this may be morally superior, it does little to salve the desire for things and places that our culture imposes on all of us. Moral superiority, intellectual esotericism, the critical sensibility, these are the sirens of most academic lives. But they do not generally pay well. Most of us lump it, some of us game the system, and others of us choose to fight. Perhaps each of these responses is synthesised in our quotidian lives. Is this why old professors become dead wood? Because the dreams of the young professoriate, the resistance narratives, lose their durability when things like comfort and status anxiety intrude on our post-30 lives? Yes, indeed, perhaps. Academics, by virtue of their critical sense, are not immune to the muses of Capital accumulation. Isn’t this what a BoBo is, after all? To have one’s resistance cake and eat it too? I do not want the rigorous and boring and financially enriched life of my old roommate, the corporate drone, but I do wish for his material comfort. Growing up modestly can do that to you. Living in our rapacious society can do that to you. How one goes about this management of desire while keeping true to one’s own narrative of self is the drama of living in our little sinecure of miserablism and fabulosity, or at the very least is my drama, of the immediate moment. The meek may inherit the earth, but this does us relatively little at the Clarins counter.

7 comments:

Girl, glad to see that you have finally read Status Anxiety. I very much enjoyed reading this text and must say that Alain de Botton's analysis of late capitalism hits home on a multitude of levels . Hope you had fun with the Voice. Looking forward to your next venture north.

La Donna

xo

In his examination of the leisure class at the turn of the century, Thorstein Veblen points out how rich people in the country do not need an ostentatious display of wealth--everyone in the town knows who has money. In the city, however, you have strangers sizing you up, and you need to show-- through your clothes or carriage-- that you are indeed respectable.

While living in a college/univeristy town as an undergraduate or grad student, I felt no need to dress up. After all, your affiliation with the university made you part of an elite club. But you get to the city and there is that shock that comes from realizing that the university/college is not the center of the universe: Wall St. is. People try to judge your financial worth and hence respectability by the clothes you wear, where you live, and where you shop.

People tell me I shouldn't care what these silly folks think. And they are absolutely right. But when you do mingle with the upper-middle class as we are bound to do, you can't help but feel the slights, especially when you know that as a brown person you are more likely to be judged and made to feel unwelcome. It's not surprising that some brown folks will cling to nice clothes and accessories as a shield. Am I buying the cashmere sweater because I love the feel of it or because it makes me feel secure? Is it any wonder that people sometimes spend more money on luxury goods when they can least afford it? If they can't have the security that comes from having money, they can at least simulate this security by surrounding themselves with luxury items that represent money and status.

A Ph.D. has some prestige, but it's your clothes and the glow that can only come from expensive moisturizers and exfoilants that tell people that this brown boy is indeed "respectable."

I know: I need therapy.

As usual, great post oso.

What's cashmere?

Excellent writing Oso Raro.

Reading your piece I wondered if money (and status) aren't just one fiction we have to live through, a fiction we have to endure.

Reading your comments I wondered how can someone have internet access and not know what Cashmere is. Isn't it an old city in Nepal?

Beyong Geography

Great post . . . you've made me think about some of the status markers of our caste as PhDs of color . . . and I've noticed something horrid about myself this week at Prestigious Upper Midwestern University Library, where I've managed to land a Summer Research Fellowship (shorthand for "Pity the poor bastard, throw him a scooby snack") . . . I tend to dress like a grad student still, while around me "faculty" prance around in jackets, seersucker suits, and overall razcuache hideous clothes (maybe I need to remember that they may be anxious about their lower middle class backgrounds and that they are themselves affecting???) . . . I think dressing down because I don't want to stick out as an outsider from a midsize regional public comprehensive . . . I also want to be comfortable in the stifling heat . . . but like the other posting suggests, maybe I'm now (in my sartorial anxiety) I'm going to clutch at something to also scream that this brown boy is also respectable. Maybe we need to reread SNOBBERY: THE AMERICAN VERSION ? ? ?

Oh Jeeves, prepare the linen suit for tomorrow!

La Vickstrix

What is cashmere? Mere cash.

Beautiful writing, as ever, Oso, and very thought-provoking.

I've been thinking about this post ever since reading it several days ago, and it resonates as profoundly with me as with your other commenters.

At this point in my life, anyway (early 30s), I'm able to accept *some* of the economic differences between my friends and I--and I'm certainly still able to sniff at those classmates and former friends who have, to all appearences, sold out and who now live soulless lives. What's hard is those friends who are in-between: who are working corporate jobs that they don't love, but that they don't totally hate, either--and who still have plenty of time to read and go to the theatre, and the money to buy modest homes ("modest," that is, in New York or Boston or D.C.) and to take semi-annual trips to Italy and Kenya and Laos. They're politically and culturally aware, interesting conversationalists, and they live beautiful lives.

They're the ones who make me question my own choices.

Post a Comment