Destroy everything you touch today

Destroy me this way

Anything that may desert you

So it cannot hurt you

[…]

What you touch you don’t feel

Do not know what you steal

Destroy everything you touch today

Please destroy me this way

— Ladytron

Tonight, in a strange bit of synchronicity, Mr. Gordo asked me what I thought of the recent immigration debacle filling television screens and Internet bandwidth and radio airwaves. Oddly enough, I was working on this very post, and it gave us a chance to discuss the recent events of protest and controversy, his telegraphed through Univision, mine through the Internet. The media, the blogosphere, and even my academic conference of the last week, has been consumed in the frenzy of discussion over the national protests that began a week or two ago and continue against proposed immigration reform legislation currently being considered by Congress. This legislation, as widely reported in the print and televisual media, would make it a felony to assist undocumented immigrants (illegal aliens, or as they are being called on many right wing sites, “Illegals”), offer them medical or social assistance, and subject the immigrants themselves to felonious prosecution for being in the United States without appropriate documentation.

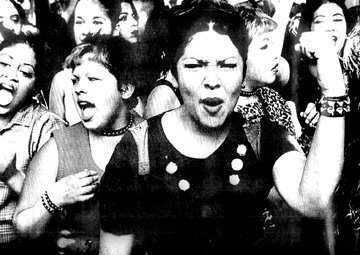

Aside from the very good chance that this controversy may in fact be a red herring to distract us from other more pressing political scandals, the response of huge swaths of the American public to the proposed legislation has been compelling. Large numbers of immigrants, their children, and naturalised and native-born Americans have hit the streets, raising their voices to counter what seems, on the face of it, not only incredibly punitive legislation, but futile legislation as well, which if I were a pessimist I would say is the only kind that gets a public airing in our bloated and corrupt capital. Especially in the right blogosphere, the publication and repetition of a series of particularly unfortunate images of Latina/o students in the eastern Los Angeles suburbs running the Mexican flag up a flagpole with the American flag (upside down) beneath has enraged many and served as a lamentable opportunity both to misunderstand US Latinas/os and express more traditional anti-immigrant and racist loathing. And true to form, the right blogosphere has been full of (ignorant, ahistorical, and racist) pop theorizations of Mexican American history, the much-feared reconquista or the Mexican reconquest of the American west, and unmeltable immigrants as the biggest threat to Mom and Apple Pie since the Red Scare. In other words, American history repeating itself, in a vicious and incoherent cycle of hysteria and hyperbole.

These flag images, which for what it's worth I also found disturbing, first struck me as a case of very poor politics. These are the images that inflame racial tensions and Anglo panic more than any other, although I understand that secondary school students are gripped by a number of emotions aside from political sophistry, not the least of which is the rush of collective power and adolescent transgression. But, on second thought, one must attempt, on some level, to intellectually understand what is going on here. Rightists claim such efforts are “girly-man” justifications, to which I would counter that such knee-jerk polemics obscure (aside from the tiresome homophobia) the tangible reasons as to why, almost forty years after the Chicano Movement, Latina/o students would be privileging the Mexican flag over the American, alterity over homogeneity, alienation over inclusion. In short, the flag images more than the protests themselves made me think we are in need of another Chicana/o Movement.

Let me preface my remarks by saying that, like most US Latinas/os, I have an intimate and profound personal connection to this spectre of Latin American immigration. I am in love with an immigrant from Latin America. My father was an undocumented worker from Mexico, an “Illegal,” who met my mother, the Nueva Mexican Española, as he was painting my grandparents' house in the early winter of 1968. In this way, my parents represented the coming together of pre- and post-1848 Mexican presences in the USA, and are not atypical of the mixed-generation profile of many Mexican Americans. I grew up surrounded by Mexican immigrants, legal and illegal, employed by my grandparents. These were, invariably, honourable people, the proverbial salt of the earth: hardworking, put-upon, struggling, striving, and surviving. These were people who, as Jesse Jackson once was fond of saying, “took the early bus”: They came to work, and work, hard and dreary and underpaid and exploitative, is what they found.

As a teenager, the summer before I was to leave for Prestigious Eastern U., I took a summer job in a paper factory arranged through the Tejano married couple next door who were floor managers at the factory, the husband downstairs on the loading dock, the wife upstairs in the packing division, which was were I was placed, at the end of the production line boxing and taping the finished products (dinner napkins, cocktail napkins, formal napkins, picnic napkins, any napkin you could think of, in a myriad of colours). Precocious and ignorant, fascinated at the time by the Bauhaus and the connection between design and industrialism, I considered the job an opportunity to discover what drove the Weimar designers and architects firsthand. The entire line, aside from my neighbor and myself, were undocumented Mexican women, “Illegals,” girls really, who were amused by my presence on the floor, the only man (boy, really) among them. And aside from the ridiculousness of a scholarship winner with a 4.0 GPA working in a factory, I learned quite a lot of what it meant to work, I mean really work, that summer. We would arrive at 4:00 am and open the windows, start the machines, and at 4:30 the women would arrive, wrapped in shawls or cute little jackets bought on Broadway downtown or Brooklyn Avenue in East LA. The line began shortly afterwards, with the women at the far end counting and arranging by colour and design, on to plastic wrapping, labeling, and finally arriving at my station, where I placed the product into boxes and sealed them with a tape machine, then loaded the boxes onto palettes that would eventually be moved downstairs. I worked a full eight-hour day, for which I earned minimum wage. Many of the women would work through their lunch hour so they could leave early, either for childcare or other jobs. The summer passed, and I too, onto PU and a different future.

That a Chicano scholarship student would taste this side of community working life is not in itself extraordinary. My mother had always worked full time, and I was fully aware of the necessity of work to survive, legal or otherwise. Everyone in my modest neighborhood worked, in offices or factories or stores or in the underground economy: drugs or smuggling or prostitution or as a coyote. This makes it sound sinister but in fact it wasn’t any more dangerous than other working class barrios in the northeastern section of Los Angeles. We had our cholos and cholas and gangbangers, but we also had scholarship students and secretaries taking AA degrees at the community college. My neighbors and friends universally appreciated the opportunity to get out of it all; to go East to PU and American success, or as my mother put it, the acceptance letter from PU in her hand, “the American Dream.” This from a woman whose family was New Mexican when it was still a Spanish Crown Colony, long before there was a glimmer of the United States in British North America’s eye. Lucky and clever Chicanas and Chicanos of my generation could chase the dream in a way markedly different from our parents or grandparents, thanks to the Chicano Movement of the sixties.

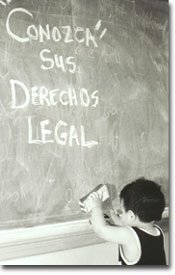

The Chicano Movement (generally, 1967-1975), the civil rights struggle of Mexican Americans, came at a period of great foment nationally. Mexican Americans, inspired by Cesar Chavez and the African American Civil Rights Movement, began their struggle as a way to find place in a country that regarded them as foreigners, trespassers, “Illegals,” uncivilized and barbaric and criminal and good for nothing. Above all, the Chicano Movement was about place, about placing Mexican Americans within the larger diorama of the United States as legitimate and equal citizens, a struggle that had begun in the 1930s but that reached a critical zenith in the sixties. Chicanas and Chicanos in the sixties did not turn towards Mexico or the United States to define their identity. Instead, they sought a third way, Chicanismo and the concept of the mythic Chicano homeland Aztlán, to articulate their state in-between, their difference yet connection to the larger American drama. Chicana/o identity is a profoundly American statement of being.

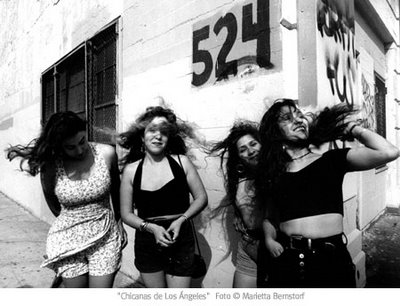

And it was towards our Movement that my mind turned when I saw the images of these students and their Mexican flags marching in the eastern suburbs of Los Angeles. The Chicano Movement was also started by high school students who staged a walk out and strike (called “blow-outs”) in several eastern Los Angeles schools in 1967 to protest the institutional and social racism that destined them to economic and political marginality. But we seem to have lost the collective thread here, the thread of Chicanismo that was such a powerful idea then and now. Chicana/o activists of the 1960s would have been highly critical of the use of the symbol of the Mexican republic to speak to their desires and needs as American citizens, as Aztlánistas, aware as they were of the derision Mexican nationals had for Chicanas/os (viz. Paz). But the social and political revolution fomented by Mexican American young people in the 1960s and 1970s and so profoundly influential in my own political and intellectual development has been surpassed by older, more reassuring but simplistic tokens of resistance to Anglo racism. And I think, this is what happens when a society delineates its revulsion as the US has with its proposed felonious solution to undocumented immigration: desperation and futility. Centre of Gravitas had a compelling post on Latinas/os and race a couple of weeks back, that for me addressed the problems of organizing around Latina/o identity, and that is our profound diversity: generational, political, linguistic, racial, sexual, economic, educational.

Yet, what’s old is new again. US society seems once again to be focused on the “problem” of Latina/o immigration, “Illegals,” without either a sense of political economy or an understanding of the empirical effects of asymmetrical economies on human migration. My doublegood Sister Disco in Minnesota forwarded this story to me that seems to address the concerns in a practical manner: “Why are Americans angry at us? All we do here is work.” A number of factors have been addressed in various media: the rule of law, the effect of undocumented and desperate labour on job markets for native/naturalised citizens, criminality, and exploitation. All of these issues strike me as perfectly legitimate questions, but the tenor of the debate has given me chills. The ugly face of the old racisms that the Chicano Movement sought to displace are still there, and have now been given new life in the post-9/11 hysterical state that remains barely suppressed in this country.

Indeed, the debate, for what its worth, over undocumented immigration has seen a parade of the old shibboleths marching across the discursive stage in all their hideous glamour: the unassimilating Mexican, the rude Mexican, the ungrateful Mexican, the Mexican who insists on speaking Spanish in front of me (me!), the criminal “Indian” nature of the Mexican, the dirty and devious Spic, the brown horde stealing jobs and services from hardworking Americans. Bar the door and close the gate, we hear, with fantastical notions of high tech walls and border checkpoints and the criminalisation of a whole class of people. But it is too late for all that, for that horse has already left the barn. Some commentators have astutely observed that the response to undocumented immigration should not be to criminalise people, but to make it so that labour conditions for all workers in the USA, native/naturalised as well as undocumented, are fair, just, and effective. But it is much easier to make political hay out of the most vulnerable, those without a public voice, than to actually change the way things work here. And let’s be clear about one thing: this debate is really not about immigrants per se, for they will keep coming regardless of the risks and abuses. This is more about how we see ourselves as a society, how Americans feel about themselves, and their prospects, and who counts as a human being. Cycles of optimism and pessimism mark our history, and we definitely seem to be on a swing towards the latter, both in our public culture and intimate feelings. The old bugaboos of the "culture wars" echo here as well, with debates on American gender, race, and sexuality from the sixties returning to duke it out. What I find especially distressing is how we ended up here, for arguably the proposed legislation that is at the heart of this whole tempest in a teapot is mean and taciturn and brutalist.

It is also easier to rely on old and violent stereotypes that are essentially racial in character, than to attempt to understand why the world works the way it does. For the nature of this debate is, I would argue, profoundly racialised, a racialisation that includes anglophone US Latinas/os as much as undocumented brown people speaking Spanish. While commentators rail against the “Illegals” marching in the streets, US Latinas/os should be paying attention (and I would say are indeed paying attention, from the composition of the marches and the yak online), because it is a half-step at best between those “Illegals” and us, a slippery slope of distrust and ignorance and “When did you come here?” and “You speak English so well” and “Dirty Illegals.” The Chicana/o and the immigrant are distinct and separate categories, linked by racism and marginalisation, which is why so many Chicanas/os serve as advocates for undocumented immigrants, because our communities are so often treated similarly, and in many ways overlap and merge, through marriage, cohabitation, and ethnic identification.

I could repeat here the statistical reassurances on the rate of linguistic and cultural assimilation for New Americans, but will leave that work to the intrepidly curious. For if Anglo Americans truly wanted reassurance on the inherent assimilation principle, they only need to look at US Latinas/os, who speak English perfectly well, have imbibed the myths of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, have lived their entire lives within the provenance of the American God of Mammon and Manifest Destiny and the Brady Bunch, and are still struggling with chasing the American Dream, from either the position of marginalisation or success.

What young Latinas/os today need, seemingly, is their own epiphany, their own Chicano Movement, which will make sense of their presence in the United States, their identity as Latinas and Latinos within a changing and dynamic multi-racial and polyglot American society, as well as a position of critique that enables them to confront racism and xenophobia and discrimination. This is what all us US Latinas/os who yearn to be free need, and what indeed is happening, in fits and starts as the very term Latina/o comes into focus, into being, as a pan-ethnicity, a classic American maneuver. US society hasn't generally liked the changes wrought by immigration, historic or contemporary, and it certainly hasn't liked its historic communities of colour very much. However, in the classic spirit of American optimism, these conversations and arguments can lead to the creation of new, dynamic Americanisms that triumph over the fears and panics that typify our rocky history. The irony of the impending Congressional legislation and the unsightly racism it has unleashed is that it may become one key to this cultural formation, this new state of being, this uniquely American creature: The Latina/o.

10 comments:

I am for legal immigration and I think that most Americans are as well. However,I am not insensitive to the plight of "illegals" who are already here. Something must be done about their plight. I am, however, disturbed by the Mexican flags and the upside down American flags at rallies as well. It seems that the further a lot of Mexicans get from Mexico the more they wave the Mexican flag which begs the question. If Mexico is so good why did they leave in the first place ?

Paul:

If St. Patrick’s Day is so great, why did the Irish leave Ireland?

Oso:

See? I knew we would be BEST FRIENDS! This is a great post.

One of the things that shocked me recently was a proposal to strip children of immigrants born in the U.S. of their citizenship. How far back would they go with that? The Reagan-eighties are back with a vengeance.

This new legal threat is truly appalling and even somewhat surprising to those of us jaded for life from living under Reagan-Bush-Bush. The labor issue is always so carefully varnished by the right and not carefully enough explored by the left that I'm especially pleased to see you address it so handily here. Thanks for this outstanding post.

hey, u should send this to www.marccooper.com, where there is a lively debate on immigration going on right now..cheers

I have no problem with immigration reform. My problem (and I think it's sort of what you're saying, Oso) is the way we go about it. It's all screaming about "the Mexicans are going to steal the Southwest (back)!" and "the damn Spics are taking our jobs!" and "they won't speak English!" It takes a serious issue and makes it the same old crap.

On the flying of assorted flags, Jesus's General has a great letter http://patriotboy.blogspot.com/2006_04_02_patriotboy_archive.html#114413379152791975

I liked your statement about "this cultural formation, this new state of being, this uniquely American creature: The Latina/o."

-what I would suggest is thinking about/linkages with that *other* uniquely American creature: the Metis.

A pan-mestiza movement...?

Oh gosh. It is so sad to have to point out that, apart from First Nations/Native Americans, every wo/man jack in the U.S. is an immigrant, whether voluntarily or not? So let us get some perspective. Legality/illegality is some arbitrary line drawn by people who need to create specific criminal classes...come on everyone, haven't you read your Discipline and Punish. This whole furor is a nonsense debate.

The question revolves around the severe drain on our support systems for those who are here "without"-health care.welfare,and all the other services that are provided by the shrinking tax base. The system is collapsing and it is ripe for a 1918 style revolt as in the Russia of old. The pyramid has now inverted-the few cannot support the many. Viva Che!!!

What young Latinas/os today need, seemingly, is their own epiphany, their own Chicano Movement, which will make sense of their presence in the United States, their identity as Latinas and Latinos within a changing and dynamic multi-racial and polyglot American society...

Fortunately enough we are in a very American way becoming more of a community.....

. The irony of the impending Congressional legislation and the unsightly racism it has unleashed is that it may become one key to this cultural formation, this new state of being, this uniquely American creature: The Latina/o.

..

ding, ding, we have a winner!!! I have never seen such a unifier between different strands of Latinos in the US in. It crosses generations and nationalities. And it comes at a time when things like Reggaeton and Spanish Hip-hop music are creating common threads within Latino youngsters across the country.

For if Anglo Americans truly wanted reassurance on the inherent assimilation principle, they only need to look at US Latinas/os, who speak English perfectly well, have imbibed the myths of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, have lived their entire lives within the provenance of the American God of Mammon and Manifest Destiny and the Brady Bunch

Forget Mammon think MTV. I am amazed at lemmings who complain about young US Latinos becoming some sort of un-assimilated horde of the pseudo-Quebecois or reconquista fifth column , while their counterparts in other countries, decry how "Americanized" THEIR youth are becoming.

Get your average 8 yr old, 1st generation or fresh across the border, who will watch the same TV his/her little classmates in 3rd grade watch. Five years later, this kids speech and mannerisms will more than likely be undistinguishable from that of other kids in Des Moines or Sarasota. And even if it isn't, they will be able to effectively communicate with these other kids.

Call it the strip-mallification of America, but it is nonetheless a powerful cultural unifier.

Post a Comment