Prancilla and I spent yesterday afternoon at an organizing brunch for LGBT community folks here in Cold City. It was an interesting kaffee klatch, with several topics on the table that folks wanted to organize around, including marriage, youth issues, and healthcare/HIV. The usual organizational/activist chatty Pattys took up a certain amount of the conversational dance floor, and I remained silent, content (somewhat) just to observe, for after all, I am a new LGBT resident of Cold City, and am not familiar with the local scene. One of the primary neuroses that came out in the discussions of the group was the paucity of role models, and how we seem to be spending our time responding to the Right rather than being more proactive. In other words, the perennial complaint of the contemporary Left. I focused on the gorgonzola-Black Forest ham quiche and tried to keep my cynical opinions to myself, although that didn’t stop Miss Prancilla from speaking up, for which she was rewarded with the dubious compliment of “being articulate” by a well-meaning white woman at the end of the session. I overheard the comment and had to stifle an eye roll. Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose. But also, I guess, Plus fait douceur que violence. We both behaved ourselves, but had a “Chile!” moment afterwards, to much giggling.

This brunch with its hand-wringing over role models, as well as a recent post over at Centre of Gravitas on the kerkuffle over Brokeback Mountain, which has been getting a lot of blogosphere attention, has led me to think about gay representation, visual media, and identification. For LGBT folks, as well as other “minorities,” the vehicle of visual representation has been our loadstar, and if one studies the history of post-1960s debates within various communities (I am most familiar with LGBT, Chicana/o, and the Black communities), there seems to be an early pursuit of the perfect image: the positive image that will not only reflect who we are, but also ameliorate the negative images known by outsiders (straight people, white people, etc.).

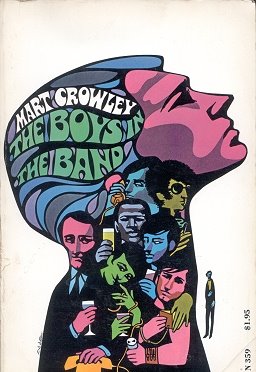

Critical work of the last twenty years or so has dismantled this sophomoric response, however understandable in a historical context, and most of us now realize the difficulty in representing that which refuses to be represented, which is to say our lives in three dimensions. For me, I have always been drawn to the darker, more problematic images that in my mind spoke to these difficulties in imagining and representing identities in visual media, things like Cruising and Boys in the Band. The positive representations of Jeffrey, Longtime Companion, and Philadelphia, struck me as flat and lifeless (I am also thinking of the Chicano/Latino film Mi Familia/My Family, which traffics in every conceivable stereotype of "the Latin," but was hailed as a critical success in representation). I feel tired of, as Hanif Kureishi so memorably put it, "cheering fictions." If I wanted to live like a saint, I would have become a nun. Regardless, films like these were hailed as “breakthroughs,” although for who was never really outlined.

Michael: Believe it or not, there was a time in my life when I didn't go around announcing I was a faggot.

Donald: That must have been before speech replaced sign language.

For me, one of the best, most life-like gay films is Boys in the Band (1970), a film directed by William Friedkin and almost universally loathed in the post-Stonewall seventies, and then eclipsed a bit by the Cruising controversy (ironically, also directed by Friedkin) and the HIV crisis. The film, based on the off-Broadway play by Matt Crowley, details one night in the lives of a several gay men at a birthday party for Hallie (Harold), interrupted dramatically by a straight (?) man. Invariably, the gay men in the film are filled with self-loathing, pathos, and liquor, by no means anyone’s idea of the post-Stonewall shiny proud gay man marching towards the sex-positive future.

Harold: You're lips are turning blue. You look like you've been rimming a snowman.

I first saw this film in college, and immediately loved it, because at the time I felt deeply alienated from gay culture, especially its focus on the body, and the sad young men of Boys in the Band seemed human to me (as well as decidedly imperfect). The incredibly queeny dialogue, with references from Tallulah Bankhead to Bette Davis, also showcased the continuum of gay camp sensibility, and its use as both an insider language of identification as well as one of pointed critique. Everyone else I knew at the time pretty much hated it, we of the Lesbian and Gay Co-Operative postering campus like mad women and pointedly critiquing anything we could, given half the chance. This was, after all, the dawn of the age of ACT-UP and mass civil disobedience, Gran Fury and stickers and die-ins and marching for our lives.

Cowboy: I lost my grip doing my chin-ups and fell on my heels and twisted my back.

Emory: You shouldn't wear heels when you do chin-ups!

But Boys in the Band, like a fine wine, improves with age. As my doublegood La Connaire once explained it to me, “When you first see it, in college, you hate it because it all about self-hate. Then, when you see it in your twenties, you love it because it’s so campy and fun. Then, when you see it in your thirties, you love it because it’s TRUE! (queeny emphasis here)” What Boys in the Band forces us to confront is the notion that perhaps our shiny post-Stonewall dreams of liberation (and the perpetual American pursuit of mental “health”) might be built on a weak foundation, and indeed we may be closer to the older, darker vision of gay pathos than we’d like to think.

Crowley’s play was wildly popular, and the film debuted shortly after the events at the Stonewall Inn in late June 1969, our hairpin drop heard ‘round the world. In this sense, the film is both a precious historic artifact as well as being slightly out of step with the zeitgeist, which was shifting rapidly at the time. Within a few months, gay men had lost the suits and ties of Mattachine and were marching down 5th Avenue kissing and having love-ins, not to mention the zaps of the Gay Liberation Front. Yet Boys in the Band is not measuring the political temperature of the time, but rather should be understood as an internal and intimate investigation of what it means to be gay. Some of these meanings, if not most of them, remain with us, if not in such an extreme manner.

Michael: What's so fucking funny?

Harold: Life. Life's a goddamn laugh riot.

For me, all the men in the film are heroes, but the character that stands out is the honourable and fabulous Hallie. The central protagonist, Michael, is much too pathetic for much identification, even by my broad parameters, and the other characters serve only as sketches of gay selves: the nelly, the butch, the hustler, the straight, the playa, the Black (OK, so Crowley’s racial politics were recherché). In fact, some critics have observed that all of the characters may serve as versions of the singular gay self.

Michael: You're stoned and you're late. You were supposed to arrive at this location at eight thirty dash nine o'clock.

Harold: What I am Michael is a 32 year-old, ugly, pock marked Jew fairy, and if it takes me a little while to pull myself together, and if I smoke a little grass before I get up the nerve to show my face to the world, it's nobody's god damned business but my own. And how are you this evening?

Hallie, along with the devilish Michael, is arguably one of the central icons of gay visual culture. He is a thirty-something “pock marked Jew fairy” (being so self-aware is a talent in and of itself) who lives to get high, yet has a razor sharp critical sensibility that throughout the film both wounds and heals. His troubled and intense love-hate relationship with Michael is the central dramatic device of the second half of the film, as the birthday party descends into chaos and Michael and his guests become more and more out of control, Hallie sobers up and becomes a keen yet sympathetic observer of this chaos, casually thumbing through The Films of Joan Crawford (a nice touch) as Michael forces his guests to play the horrific yet revealing “Telephone Game.”

Why Hallie is my hero of Boys in the Band is two-fold: Firstly, he calls ‘em as he sees him, demonstrating the queenly art of the “read.” For those of us versed in this complicated cultural sensibility, it is a weapon that can both empower and viciously wound. The ability to “read” is a gay talent partially grounded in being raised in the belly of the beast, as LGBT people are born within the heterosexual family. We learn very early not only how to hide our true selves (and to lie brilliantly while doing it), but also to critically appraise the distance between truth and image. Reading brings these two back together, most of the time violently, since people generally prefer to live within their fantasies of what is true, rather than truth itself. The “read” is like Windex for the soul, although it can and does leave streaks… of blood! Meow!

And Hallie, played by the brilliant Leonard Frey (who went on to star in the über-haimish Fiddler on the Roof, believe it or not), is, like Michael, an astute and talented practitioner in the sisterhood of the read. This is the dramatic device that drives the tension between Michael and Hallie, as they tread carefully around each other until the end of the film, when Hallie must step up to the plate and deliver the read of all reads. As Michael’s party has collapsed into tears, drunkenness, and sloth, Hallie gives a drunk and out-of-control Michael the read of all time:

Harold: [Michael,] You're a sad and pathetic man. You're a homosexual and you don't want to be, but there's nothing you can do to change it. Not all the prayers to your God, not all the analysis you can buy in all the years you've got left to live. You may one day be able to know a heterosexual life if you want it desperately enough. If you pursue it with the fervor with which you annihilate. But you'll always be homosexual as well. Always, Michael. Always. Until the day you die.

After which Hallie swivels on his heel and announces, “Ah, Friends! Thanks for the nifty party!” Ouch! That one hurt, Miss Hallie! Michael, of course, soon descends into hysterics (after picking up the pieces of his face!), pill popping, and out to search for a late Mass. Hallie has kept it real, and zeroed in on the ideological undercurrent driving the rancour of the party. Interestingly, as gay critics considered this film a vehicle of self-hate, Hallie’s read specifically identifies that self-hate as the central problem of Michael, himself, and the other gay men of the party. He offers no flower-laden solutions, rather his read suggests that becoming comfortable with one’s sexuality in a coercively heteronormative society entails constant struggle to “get right.” And what LGBT person could deny this simple, elegant little point?

But alongside the talent of the read, which alone can be devastating, is Hallie and Michael’s relationship, grounded in the power of gay friendship. We tend, in gay popular culture, to focus on romantic love as the fulfillment of our innermost desires and dreams. At this very moment, there are thousands online, in bars, at yoga class, in supermarkets and malls, discussion groups, in bathhouses and parks and bushes and softball games searching for that utopian contentment. Yet, what has always struck me as more crucial, more important to becoming ourselves in a communitas, is friendship: the friendship of other lesbians, gay men, bisexuals, and transgendered folks. Las girlfriends.

There are two key moments in the film that speak to this concept of gay friendship and the bond it entails between Hallie and Michael. One is when the gifts for Hallie are being unwrapped: Michael’s gift is a mysterious framed photo of himself, with an inscription. As Emory, the ne plus ultra nelly, queries as to what the inscription says, Hallie responds that is “just something personal” as he quietly re-wraps it and he and Michael exchange a poignant look. Nothing more is said regarding the gift, but it is an interesting and mystifying marker of something powerful between the two men. The other, arguably more powerful utterance is when, after his devastating read, Hallie leaves, loaded with his gifts (including the Cowboy hustler purchased for him by Emory). After the wreck of the party, after Hallie’s ruinous read of Michael, after the tears and screaming and fist fights and oh-so-many cocktails, Hallie says quietly to Michael, “I’ll call you tomorrow.” This scene always left me with tingles down the nape of my neck, for it speaks to the greater bonds we create with our girlfriends, our bonds as gay and lesbian people in a society that hates our very being. Some I’m sure will think it speaks to the socio-pathology of co-dependence, and perhaps it does, it we wanted to read it in a therapeutic frame. But human emotions, community, and identifications are not rational, rarely purely “healthy,” and are messy, complicated, and multi-layered. In this focus on friendship, Boys in the Band also presciently anticipates the literary focus on the strength of gay friendship in the work of Kramer, Holleran, and Mordden, paradigms of seventies gay literary sensibility. What I see in this powerful conclusion is gay friendship: the alliances and communities we form outside of the biological family, the networks of support and sustenance that enable the very notion of LGBTQ.

Frey, like many of the principles of Boys in the Band, died of HIV disease in 1988. So, the real life cast of Boys in the Band reflects as well the progression of the gay community through the utopian seventies and the trauma of the HIV crisis. But, thankfully and gratefully, celluloid is forever (although we are still waiting on the DVD), and Hallie, Michael, and the “boys in the band,” remain present and fondly remembered as the imperfect, human representations they are. In the nineties, opinion started to turn, as it invariably does, back towards reading Crowley’s play and Friedkin’s film generously, both as a historically specific representation of gay time and space, as well as revealing continuing elements in gay culture that are at play in contemporary LGBT culture. No representation is perfect; that is a formal impossibility. But Boys in the Band offers us a gay-themed and gay-centred social worldview that can, if we listen carefully, tell us something about ourselves, where we have come from, and where we might be headed, succinctly contained within Hallie’s phrase, spoken as she confronts the “straight” interloper Alan, with grand queenly style: “Who Is She? Who Was She? Who Does She Hope to Be?”

7 comments:

Yes, it needs to be revived and appreciated. My favorite in the "Drucilla tells it like it is gay party" genre is WHo's Afraid of Virginia Woolf, which is coded, true, but also manages to take down the fags and the straights, in an all-out, Mrs. Danvers-style conflagration. Get the Guest, anyone? Or will it be Hump the Host?

I like this post, though I don’t agree with it entirely. It’s too hard for me to remove films like Boys in the Band from their historical context. That’s just the historian talking.

I take your point, though, that BITB shows a sense of community amongst queer folk not often seen. Much like images of straight women, most visions of queer men show them in competition or at bitchy-odds with each other.

Representation is a key issue for communities who are often not represented. So we cling to the few images that even hint at our actual lives. On a side note, look at how rarely GLBT images cross over with Chicano/a images or Black images.

I'm not sure about Gayprof's side note. I'm not an expert on chicano representation but it seems to me like all the chicanos, at least in Academe, are queer. If I list by heart prominent chicano intelectuals I will say Richard Rodriguez, Gloria Anzaldua, Teri de LaPena, Cherie Moraga...

Guarandol: Yeah, I have noticed Chicano studies does seem to have a vibrant queer contingency. Someone should explore why that might be the case.

Rather, though, I was referring to films and other forms of popular culture. In other words, it seems to me that most GLBT films lack Chicanos and most Chicano films lack GLBT folk.

Yes,Gayprof, I see your point. It seems like in American Academe standards you have to be queer to be an intellectual.

In the film Transamerica, the first time we see Bree living her normal life after the surgery, she is dressing a "Mexican attire" to match the vernacular decoration of the restaurant where she works as a waitress. I know that she is hardly a chicana but it is interesting that after her gender was restored she still has to perform an identity... One wonders "Who Is She? Who Was She? Who Does She Hope to Be?”

I've just seen the movie for the first time ever (I'm a 20 year-old student) and, as a young gay man who's also very interested in gay movies and gay history, I thought it was extremely interesting.

I completely agree with your analysis of the movie, especially of the "friendship" part. Though I think it's a pity you "missed" the relationship between Donald and Micheal, which I think is also a great representation of this queer phenomenon of the best friend/ex-lover/fuck buddy...

Anyway, I think just like you that this movie has been vilified without reason. Yes it shows self-hatred, but only to denounce it. I think that the way it was reviled in the post-Stonewall era is a sign that the movie hit too close to home for many. No one likes to have their own flaws reflected to them too clearly - an issue the play also adresses... For me it was also a matter of "this is what you are - change it", which was taken as provocation in the gay liberation movement of afterward.

Anyway, I could go on and on, and I might rather write my own review. Thank you for your hindsight.

You forgot Michael's attempt to read Harold ("You starve yourself, all day, living on coffee and cottage cheese, so you can gorge yourself on one meal, and then you feel guilty... And this pathalogical lateness... standing in front of a bathroom mirror, for hours and hours before you can walk onto the street, and then looking no different..." and then attacks Harold for using tweezers to mutilate himself trying to clear his pores and hoarding sleeping pills (for a suicide?), before finally pronouncing telling him, "Not all faggots bump themselves off at the end of the story!" Harold even then one ups him by stating, "What you're saying may be true. Time will undoubtedly tell. In the meantime, you left out one detail: the cosmetics and astringents are PAID FOR, the bathroom is PAID FOR, the tweezers are PAID FOR, and the pills are PAID FOR."

Post a Comment