"The Island of Montreal (in French, île de Montréal), in extreme southwestern Quebec, Canada, is located at the confluence of the Saint Lawrence and Ottawa Rivers. The island is approximately 50 km long and 16 km wide at its widest point. It has 266.6 km of coastline. Some 26% of the population of Quebec live on the island."

Today is my last full day in Montréal. Tomorrow I return to Cold City to begin the long, inexorable slide into summer. As always, end-of-trip days are full of the last minute social and shopping errands, as well as laundry, packing, and departure planning. As well, final days are full of the ambivalent feelings of leaving a city and friends I feel deeply attached to, as a vision of urban living and a distant personal goal of living again within her borders. I am, decidedly, a fierce partisan for Montréal.

"The first French name for the island was "l'ille de Vilmenon," noted by Samuel de Champlain in a 1616 map, and derived from the sieur de Vilmenon, a patron of the founders of Quebec at the court of Louis XIII. However, by 1632 Champlain referred to the "Isle de Mont-real" in another map. The island derived its name from Mount Royal, and gradually spread its name to the town, which had originally been called Ville-Marie. In the Mohawk language, the island is called Tiohtià:ke Tsi (a name referring to the Lachine Rapids to the island's southwest) or Ka-wé-no-te."

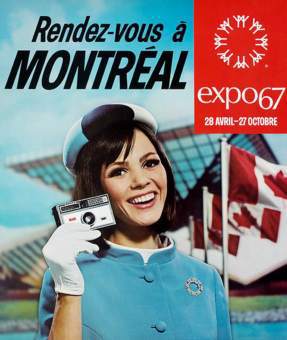

My first knowledge of the city came from an old National Geographic magazine I had as a young teenager from 1967, which had a long article on Montréal, Canada's centenary, and Expo '67, Montreal's apex as an urban and socio-political idea. I remember being fascinated by the piece, which in retrospect was mostly fluff, but the image of the cosmopolitan, bilingual and sophisticated city stayed with me over the years as an idea. It wasn't until a moment of crisis in my doctoral studies where I, stuck in San Francisco and depressed and seriously pondering quitting, decided to move to Montréal, on a lark. A contact at a university here provided a "research fellowship" which was really a glorified library card, and within two months I had sold everything that couldn't be moved in a box, signed a lease, and woke up in my urban ideal, somewhat confused as to why exactly I was here.

"The Communauté Métropolitaine de Montréal covers 3,839 km² (1,482 mi²), with 3,431,551 inhabitants in 2002. The Census Metropolitan Area of Montreal (also known as Greater Montreal Area) has a population of 3,635,700 in 2005 according to Statistics Canada ([3]). A resident of Montreal is known as a Montrealer in English and a Montréalais(e) in French."

That year was crucial, in that it reenergized my doctoral work, introduced me to the city, and left me, after I returned to the United States, with several close friends in the city to which I would return year after year. My original time here was not spent working academically so much, per se, but rather in a refreshing dissipation which has remained one of the hallmarks of my impressions of the city: drinking, smoking, eating, and going out. The catholic qualities of living that are so demodé in the rest of North America.

In fact, life in Montréal reminds me of the scene in the film Funny Face where the editors of the top fashion magazine decide to stage a shoot in Greenwich Village, and they declare as they decamp in cabs for George Washington Square, "Let's go to one of those sinister places in Greenwich Village!" It has the largest population of college students in North America, and can on occasion feel like West Berlin before the fall of the wall: a place where young people go to avoid life, the draft, and drink like fishes. On this trip, as always, my Cicero has been my doublegood girlfriend La Donna, famous for his boycraziness, on an endless circuit of bars, dance clubs, and restaurants. Recently, two distinct phases of my personal life here have come together, as La Donna is now close to my other doublegood in the city, The Voice, and they are now (surprisingly, pleasantly, and with some chagrin on my part) partners in crime.

"Montreal is the hotbed of culture for French speaking Quebec and Canada. Unlike other North American cities which serve their suburbs and hinterlands, Montreal plays a national role in the development of Québécois culture. Therefore its contribution to culture is seen as a state-building endeavour rather than a civic duty. The cultural divide between Montreal's Francophone and Anglophone culture is strong and is referred to as the Two Solitudes. The Solitudes are strongly entrenched in Montreal, splitting the city geographically at St-Laurent Boulevard. Few elements seem to cross this border."

La Donna and The Voice were both met, not surprisingly in Montréal, at house parties. While living in Montréal is as living in any large city, to be an English-speaker within its boundaries can sometimes feel like living in a small, manageable city. Sometimes when I lived here, it seemed even smaller. The continuation and strengthening of my relationships to La Donna and The Voice represent not only the precious connections between people (they are, arguably, two of my closest friends, even though we have not lived in the same city for almost ten years), but also the power of the ideal of Montréal for me: Here I have lived, continue to inhabit (in visits and spirit), and one day shall live again.

As usual in my visits to the city, I have been out too late, smoked too many cigarettes, drunk perhaps a wee bit too much, and have taken one too many taxis to get where I need to be. I have spent good times with La Donna, The Voice (and her new and delightful gal pal), and LoLo, another old friend from my former days here. New York City may never sleep, but in Montréal, one enjoys. The gastronomic and shopping pleasures of this northern metropolis have always been ones I have compared to New York (unfavourably to the latter), and indeed when Mr. Gordo and I were at home at Sadistic College, going to the City for him meant New York, and for me Montréal.

This tale of two cities is one with a parallel in history. For much of the nineteenth and early to mid-twentieth centuries, New York and Montréal were twin cities, in many ways, sharing social sets, architectural and urban styles, and financial and cultural prominence on their respective national stages. Both have suffered from the changes wrought by post-industrialization, but Montréal's status has declined more precipitously than New York's, for a number of reasons (the independence debate, francophone nationalism and political instability, the Saint Lawrence Seaway, evil Toronto).

In some ways, this has saved Montréal's character, highly specific, from the mass of bland consumeristic capitalism that may make Toronto a nice place to live, but utterly boring as well. Montréal is a city of edges, tensions, and negotiations. The first, primary one is between English and French, but more contemporary dramas of race, ethnicity, economics, and sexuality have diversified this primal drama. Yet, in many ways, the tension between English and French (language and people) remains the city's loadstar.

Indeed, one of the most important things that drew me to Montréal both personally and intellectually was its quotidian reality of negotiating linguistic and cultural differences. The original academic impetus was to compare this historical and contemporary condition of bilingual and bicultural reality to potential Latino cultural citizenships in the USA, which is what I focused on while here, reading a lot of Canadian and Quebec cultural and social history, and testing out this knowledge on the streets, in the Metro, the cafes and restaurants and social spaces of the city. It is not that this process is perfect, for in fact it is not. It is constantly contested, and rocky, and difficult terrain. But, it does work, in a strange way.

I discovered most of this at an interesting time in the city's history, for I arrived shortly after the last referendum on provincial sovereignty-association (aka independence for Québec), when the mood in the city was desultory and depressed. Rents were low, as well as the price of Canadian beer, and I spent the year mostly pickled and suffering from a series of well-placed health and financial crises that can only, in retrospect, be described as bittersweet.

This bittersweetness can sometimes be extended to a description of the urban culture here as well, a sense of missed opportunities and unrealized potentials. Recently at the Canadian Centre for Architecture, I saw an amazing show called Montréal Voit Grande (Montréal Thinks Big), which examines the go-go sixties here, where development was the watchword and the city conceived of itself as the continued major metropolis of Canada, with appropriately grand architectural and structural gestures. The show also featured the amazing aerial photography of Olivo Barbieri, one of which is featured above (of Place d'Armes). This notion of national and economic centre did not come to pass, but its effects speak to the potentials of Montreal as well as the optimism of "thinking big," and the period has left us with a number of useful and prescient projects, such as the Metro. I think Montreal's "Big" period can actually be divided into two parts: the Anglophone business establishment's post-war development plans (roughly 1950 to 1970), and the Francophone nationalist desire to turn Montreal into a showcase of French economic and cultural power (1964 to the present, really, but I am thinking more 1980). Both of these periods have given the city some excellent examples of monumental architecture (Place Ville-Marie, Place Des Jardins, some of the buildings at Université de Montréal, Mirabel Airport) and urban design in the service of ideology (capitalistic, nationalist, linguistic, or whatever) that can sometimes seem like the ruins of the Coliseum: souvenirs of past visions of the future, which has annoyingly (as all futures) gone its own way.

"This [bi-lingual/bi-cultural] aspect of Montreal culture makes it an evolving environment where anything can happen."

In the contemporary period, the political battle for Montréal has been, in the dream of some francophone cultural nationalists, to turn it into a francophone city on the model of Paris. This desire stems from the brutal discrimination Canadian francophones suffered leading up to the Quiet Revolution, the cultural and political awakening of francophones in the sixities. But, like all cities, Montréal is a complex nexus of histories and desires, and it has refused to become a simple pawn in this struggle. It has historically been and remains a "borderlands," a meeting place for different people, languages, and customs that meld and fight amongst themselves within the urban space. And these tensions give it a unique energy which draws me back over and over, and continue to make Montreal, in the words of an city slogan when I lived here, "c'est toi, ma ville!" even if current circumstances force me to remain at a geographical distance.

Demain, on regagne la vie quotidienne de Cold City. But in this moment of pre-modern political dramas and the assault on cosmopolitan ideals, Montréal, like other cities, gives us a vision of the lived experience, the negotiations and demands of acknowledging and existing within the chaos, maelstrom, and joy of difference and diversity and urban citizenship, and these qualities we need to stand up and defend with all our might, as they are inundated by forces of medieval barbarism. Our lives depend on it. We all need to become partisans for the ideals of Montréal.

1 comment:

I love Montreal. It's not just a diverse city in terms of Anglophone vs. Francophone, but also has multiple international communities. Plus, it has one of the best queer neighborhoods I have ever visited.

Enjoy your last day there!

Post a Comment