The test of a vocation is the love of the drudgery it involves.

— Logan Pearsall Smith

Yesterday I had a delightful brunchicito with Prancilla, who always seems so busy on Sunday mornings, by the time I rise for a late bleary-eyed brunch she has run several marathons, saved several children from oncoming buses, and scrubbed her kitchen pots clean! I honestly think if it weren’t for Miss Prancilla, this girl would be in a well-padded booby hatch by now here in Cold City, without the late brunches, shopping outings, and freedom to be a fabulous girl with an equally fabulous girl. Revelatory of the ways in which the academic world turns, Prancilla and I met when we were on the same panel a couple of years ago at an otherwise wet noodle of a conference, and our meandering pathways have led us both through the Bay Area (separately) and now here to Cold City. Sometimes academia feels like three degrees of separation: Your advisor, your doublegoods, and your arch-enemies.

We talked, as I nibbled on Eggs Benedict and Miss Thang inhaled some major carbos with barely a hiccup, about the blog (“I can't believe you wrote about our penis discussion!”), about professional and personal writing, about the profession and about our roles in it, plans for the future, and the potentials and limitations of the academic milieu for our personal and political projects. To paraphrase Mother Abbess in The Sound of Music, when God closes a door, does He really open a window? Or are we all waiting around for our Captain to come and turn us into haimishly dressed folksingers? While Maria may have her comely charms, who doesn’t really want to be the sophisticated yet tragic Baroness instead?

In so many ways, our professional dreams can mimic disastrously the emotional dynamics of the family and institutional hierarchies: of “good” and “bad” girls, of team players and alienated sullens smoking under the bleachers. Since most of us were, in the halcyon light of youth, those very sullens if not smoking then plotting, the university can become our normality, our proof that we are indeed worthy and valuable, even if we didn’t have white teeth, clear complexions, and cheerleader girlfriends and quarterback boyfriends.

Academics, for as rational as we claim to be, often forge intense and completely irrational emotional identifications with our institutions and our jobs therein. This is one reason as to why our institutional politics tend to be so pitched. For many academics, teaching and research and service, the unholy trinity of la vie academique, aren’t just a job description, they are who we are. This critique could be extended, as one of my witty seniors in my thesis seminar did today, to US society in general. As some wag said somewhere else, some other time, we Americans don’t work to live, we live to work. I think this work ethic can be more intense for academics, because we become the living vessels of our training at the head of the classroom or on the journal page or the manuscript frontispiece. This close association of the personal and professional can, under unscrupulous management (deans, presidents, department chairs, students), be devastating when we are shown or choose the door, because the end of the job so often can also mean the end of us as personal and professional beings.

I have been thinking a lot about ambivalence and our profession, in particular the challenges of negotiating the crucial distinctions between oneself and one’s position as a professional intellectual (i.e. a professor). Specifically, is there room in the order of academics for insouciant dissenters who yet still offer the faith something, if not fealty than perspective at the least? This thinking has been part of my process in dealing with my insane and utterly horrible experience at Sadistic College as well as adjusting to my new gig at Cold City U., and more largely my relationship to academic practice in general, which is also one of the reasons I started this weblog.

This collapse of the personal into the professional in academia is an unfortunate historic legacy of our profession as a vocation, dating from the monastic origins of the university as an endeavour linked to religious expression. The joining of job/institution and candidate reminds me (among other things, which is the subject of a forthcoming entry) of a religious order, for joining the order of academicians is full of the Catholic rites of mystery and abjection: a renunciation of worldly and material values, a commitment to a life lived within an intellectual practice (in one case, the belief in God, in another the belief in the realm of ideas, in both an overriding confidence in the truth of the word), and a monastic sobriety that brooks little dissent.

As modernity and technology changed the conditions of society, the university adjusted as well, but has ironically maintained some of its most medieval structures of apprenticeship, training, and subjection in its hierarchal structures. The rub, of course, is we no longer live in medieval societies, and the rigorous training and long period of apprenticing for positions that no longer exist and will never (contrary to eternal claims of rising enrollments) exist again, have informed the turn, finally, in academia to thinking of ourselves as workers, not acolytes. Hence, the move in the late twentieth century, which is accelerating (rockily, unevenly) now, towards unionization and labour organizing in the academy.

As anyone familiar with these issues can attest, this turn has been not only remarkably controversial but also resisted forcefully by entrenched forces in the academy that realise the dangers that the self-conceptional shift away from vocation towards labour poses to their own personal power as potentates in "The Shop." And to be fair, many academics have at the very least honest questions about thinking of ourselves as workers as opposed to practitioners of the academic faith. How does labour organising affect our work with students, via grading, evaluation, and academic freedom in the classroom? How can we approach teaching, research, and intra-institutional and professional evaluation from the standpoint of labour? How does this move affect university and faculty governance, and how we relate to each other as colleagues?

These are legitimate concerns, but they all are to a certain extent grounded in a series of problematic preexisting self-conceptions that remain unquestioned. Primarily, I think, two of the most entrenched forces working against unionization and labour thinking in the academy are snobbery and the mystification of vocation. Academicians think of themselves as white collar, highly educated professionals, with little in common with traditional images of the unionized worker, i.e. blue collar industrial drones. In fact, you hear that a lot around questions of unionization: “We don’t work in factories!”

Well, Mary, we might not be working at the looms, but have you been to a modern university lately? Most public R1s and R2s are proverbial knowledge factories. Tell me what kind of personal interaction and guidance can happen in a lecture of 500 or 1000 students? Or even in “small” seminars of 30 people? If this is not the mass production of brains, I don’t know what is. Even the private colleges and universities that attempt to foster individual relationships between students and faculty through low faculty-student ratios suffer from the increasing consumer-driven attitudes of students and parents which attempt (and depressingly often succeed) in turning professors into overeducated shop girls.

Distance learning initiatives and the rise of for-profit diploma mills also threaten not only the most vulnerable in our bookish clan (adjuncts, contract workers, and graduate student workers) but also the tenure-lined elite. If we do not negotiate this technology carefully, we could all find ourselves in short order to be video images projected on a screen, and without tangible work. This is one good reason why it would pay to start thinking of ourselves as labourers, and not cognoscenti, because these transformations are coming whether we like it or not. It is better no doubt to be prepared rather than caught unawares. But in this case, being prepared means toppling a whole regime of self-conceptions and self-delusions that most likely will not happen anytime soon.

As I have noted before, or all its liberal intentions, the university is a remarkably reactionary place, and comparisons between academics and workers strike many as an untoward leveling. But this critical position, in my mind, speaks to a problematic desire to not be associated with “those kind of people,” although scratch an adjunct or a freeway flyer to get a glimpse of 19th century factory hell in its 21st century academic variation: no benefits, no job security, no academic freedom, and no time to complete any of your own research. We so firmly believe in the Ivory Tower because many of us need to, desperately: we have sacrificed many years, emotional energy, and in some cases a lot of money to rise to the top, to scale Mount Everest and get to the Valley of the Dolls. We have, in other words, a lot invested in our distinction as intellectuals. But that investment in distinction may lead, ironically, to our extinction as a specific knowledge class. As my doublegood girlfriend The Fierceness says from a different, francophone Ville Froide perch, “Knowledge today is too important to be left to the University.”

The social and class snobbery associated with anti-labour feelings in the university is concomitant with a mystification of the profession that together go hand-in-hand to solidify and reaffirm the monastic tradition of the university as sacred practice (and hence, immune or highly resistant to the secular, profane nature of labour).

Vocation is defined as, “an occupation, either professional or voluntary, that is seen more to those who carry it out than simply financial reward. Vocations can be seen as providing a psychological or spiritual need for the worker, and are often assumed to carry some form of altruistic intent. The term can also be used to describe any occupation for which a person is specifically gifted, and usually implies that the worker has a form of ‘calling’ for the task.”

Most of us, for better or for worse, have this relationship in some way to our profession, especially teaching. It is a calling, a talent, a sophistry not understood by outsiders. In short, the traditional formation of the intellectual, dependent on omniscience, specifically on being different from those around us, special, the intellectual elect. To break away from this model, to descend into the quotidian, both threatens the personal investments we have in thinking of ourselves as an elect, and doubly threatens the wizards behind the curtain who rely on this mystification to run the industry that is the university. Does that mean we have to lose the best aspects of vocation: dedication, service, talent, community, and responsibility? No, but it does mean we have to renegotiate the terms of these conditions in the harsh light of the ruins of the university, as Bill Readings put it.

If we continue to uncritically believe in this mythic infrastructure, we arguably risk our future as professionals and intellectuals. Is the solution to pop out of our medieval dreams into some sort of Marxist fantasy of workers' collectives, like a girl in a cake, sui generis? Of course not.

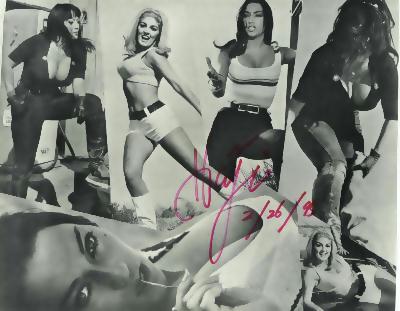

However, we had better start dismantling and examining our histories ourselves, and making sense of what intellectual practice is at this moment, and engaging critically with the issues that confront our profession (including labour and exploitation), and finding our voices somehow, or it will be done for us, and I promise you the results will not be pretty. We cannot rely on God to open our window for us, you and me and Maria and the Baroness all together have to get our proverbial shit together and pull a Faye Dunaway channeling Joan Crawford: “Tear down that BITCH of a bearing wall and put a window where it OUGHT to be.” And as the shit-kicking, lesbian lovin', karate-chopping gals of Faster Pussycat remind us, we can do it in style, chamas!

Or as my old, old and long lost girlfriend Miss Truffles once put it, upon seeing a blonde heiress of Prestigious Eastern U. obliviously bopping along to her Walkman on a dark street at night in front of the WaWa during one of our many crime waves in the fall of 1989, “Honey, (George Michael’s) Faith will not get you over!”

¡Adelante!

2 comments:

I always wanted to be the baroness, she gets the only ironic line in the film, "Why Max, you should have told me . . . To bring along my harmonica!"

So excellent! That line could also serve as a koan for aspects of academic life.

Post a Comment