Inspired by a recent post on the incomparable Doris Wells by Mr. Gordo, as well as an offhand email reference (Margo, baby) by GayProf over at Centre of Gravitas (along with his Lynda Carter/Wonder Woman theme: Go [Güera] Latina Power!), I've been thinking lately of the Star, and her (typically it is a her) relationship to gay self-conception. Like most gay men, my life has been influenced by an intense indentification with the Star, whether in film, television, or music. For many of us, I think this is a complex nexus of desire, longing, mentoring, and modeling, shaped by things like race, gender, and sexuality in subtle but powerful ways.

My first Icon wasn't even a star, in the conventional visual sense. In second grade, someone, perhaps my mother, ordered a Scholastic book (remember them: sort of like Amazon for the pre-teen set, along with Dynamite Magazine) for me on Harriet Tubman. I can't remember the exact title of the little, slim volume, something like "Diary of a Runaway Slave." It had a dramatic photo illustration on the cover (in sepia, this I remember) of a shadow of a woman on a hillside, presumably Tubman fleeing for her life. For whatever reasons, the dramatic story of Tubman's escape from slavery and her return to the South as a conductor on the Underground Railroad was profoundly influential, and Tubman became, in short order, this queen's first "Star." And it was along a racial line that would become important later, a "Blatino" cultural identification with Black culture and iconography directly informed by my identity as an anglophone Latino.

In this promising beginning one finds many themes of the Gay Icon: strength, resiliancy, resistance to conventional gender norms. Controversial and complicated women marching to the beat of their own drum. All that is missing is the obvious glamour quotient. That would come later, natch, in the normal way: Classic Hollywood Cinema. My mother, for being so terrified of raising a fegallah son, was remarkably adept at providing said son with the tools of a budding gay sensibility. On sunny, dry Southern California weekends, when I would be desultorily lying around plotting the downfall of my teenage arch-enemies, my mother would call me to the television set to watch, in retrospect, a veritable GLBT Visual Culture 101: All About Eve ("A really good movie!"), Tea and Sympathy ("See? they thought he was gay too."), Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? ("Look at how horrible Bette looks!"), The Women ("Really funny!"), Mildred Pierce ("That Vita is a real bitch...") and Now, Voyager ("So sad..."), among others. Um, HELLO! All I can say in regards to this visual education in my tender teenage years is the unconscious mind exerts a powerful influence. Paging Doctor Freud! Code BLUE in the living room! At the very least I was well-prepared for screenings at the Castro Theatre.

But it is in these tender years of hesitancy, hiding, and horror that the young gay man's identification with the Star is set, for in her struggle, cinematic or otherwise, the budding faggot finds a theory of survivance comparable to his own struggle against a hostile world and home life, and comes to focus his energy on the Icon in a displacement of what he would like to do in the high school cafeteria: Tell off those sons-of-bitches who have teased him, spit on him, whispered behind his back and said it to his face ("Faggot!"), swing his fur, and march off on stilleto heels. Moreover, the big Fuck You that the Star gives anyone who has it coming (and those that don't: the tragic but fascinating failing of the Diva's search-and-destroy methodology) is a strange gay version of the American hero: The go-it-alone, independent frontier spirit, just in silken hose and a hat. The movies that my mother made me watch (bless her soul) communicated the value of fragile, human women struggling against all odds to find their voice in rooms full of hostility. And what young homo can't identify with that? Of course, most of us would sleep with those "homophobes," this time with wedding rings on, several years (and drinks) later, but that, children, is a whole 'nother blog entry altogether.

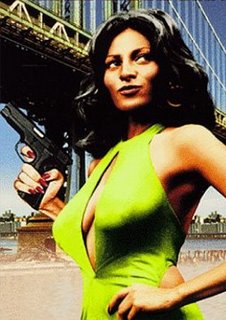

The racial inflections of the Icon grew in importance, as I left the tender embrace of Classic Hollywood Cinema, with its three-point lighting, elegant costume design and diction, and "white ladies in struggle," and became a young Chicano gay (¡y que!) activist. At this point, other more potent symbols of female resistance came into play, most prominently Pam Grier as the shit-kicking Black SuperMama of the honky's nightmare and the Revolution's wet dream. Etang Inyang, in her saccharine but thought-provoking short Badass Supermama, reveals the complexity of identification with Grier, who offers a powerful image of Black women but one that is compromised by the strange and problematic (i.e. funky) racial and sexual politics of the Blaxploitation genre. Still, Grier's "soldier for the revolution" persona as well as her presentation of glamour, excitement, and danger in some ways recast Black women and women of colour as subjects as opposed to objects, a move paralleled by women of colour feminism. Inyang reminds us that all icons, no matter how "positive" (or alternatively, negative), are complex intersections of desire and repulsion that are irrational as they are compelling. Grier's Icon is one that has grown and developed outside of Blaxploitation (although that remains the touchstone), as demonstrated in the underrated but brilliant Jackie Brown, as well as her delicious work on The L Word. As Grier ages, her new work is a scrim on the older images, and we begin to see a powerful woman in the full complexity of life through a filmic and iconographic pentimiento. Still fabulously shit-kicking, I might add.

Several years ago Daniel Harris, in his volume The Rise and Fall of Gay Culture, would examine "Camp" sensibility and its relation to the female Star Icon. Originally published in Salmagundi, his essay, which at points is quite funny, traces the rise of the Star as an object of gay identification, and (for Harris) its subsequent fall into burlesque. Unlike Harris, I don't feel that the Star has either outlived her usefulness or become a mockery. One could argue that, contra Harris, even as the Star degrades in front of our eyes, loses her glamour, and becomes a hideous warning rather than an inspiring icon (Harris focuses on Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? and Mommie Dearest in his discussion), she retains what made her attractive in the first place: humanity and fragility. The foibles of the Diva, out of control, losing her looks, and beginning her slow descent into madness and the Love Boat players, can serve to remind post-Stonewall gay men of the illusive qualities of utopia, and the attendant challenges of the move out of Peter Pan Land, although one can argue that the HIV crisis has aided this critical process considerably.

Harris joins others (like Andrew Sullivan) in arguing that old, pre-Stonewall paradigms of gayness are irrelevant in our post-AIDS new gay reality of homonormativity (although admittedly Harris is less of a proponent for this position than Sullivan). I think that this perspective is not only short-sighted, but ahistorical. If anything post-Stonewall gay struggle should demonstrate to us, the debates around gay sexuality and its place in our socio-cultural milieu have gotten more, not less, intense. And while I am quite happy some gay teens can attempt to lead normal lives, I still feel most gay youth, certainly working-class youth, remain vulnerable to the same process of terror many men of my generation went through, and therefore, the Icon will remain a powerful and central idea for gay men, even if the actual icon herself shifts and changes.

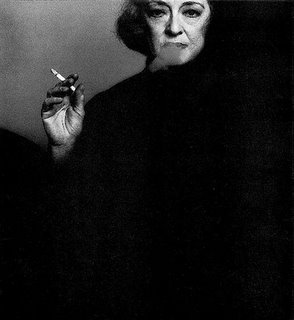

I am reminded of the character of Huma ("Smoke") in Almodovar's Todo Sobre Mi Madre, itself a recasting of the iconographic classic All About Eve. On her dressing stand is a picture of Bette Davis enveloped in smoke (the image above), older but still powerful in her visual presence. Huma, played by the incomparably fabulous Marisa Paredes, relates in another scene of her identification with Davis as a young woman, learning how to smoke and changing her name to match the iconographic quality of Davis, cigarettes, and feminine empowerment. In some ways, we could read Almodovar here as referencing those other, non-biological mothers so crucial to those of us who needed, and may still need, mothering of an unconventional sort. "All about my mother" speaks not only to our real mothers (complex enough) but to those other women (and men) who have mothered us, guided us, and provided succor when there was none. And to these Icons and real people, the paradigmatic mothers of our elegant refusals and resistance, I honour you!

5 comments:

No Auntie Mame?!?! Your mother deprived you. *hehehehe* I really think Rosalind Russell, via The Women and Auntie Mame is the quintessential, though often overlooked (due to the long shadows of such divine women as Bette Davis and Joan Crawford), gay surrogate mother.

I still want to be Bette Davis. Like you said, the thought of being able to eviserate my enemies, while smoking a cigarette and decked in furs, with my adamantine wit is just the ultimate fantasy.

Hail, Amazon Sister!

I loved this post, chica. Where, though, are the Golden-Age Latina Divas? What about Dolores del Río or Lupe Vélez? Problematic figures? Yep. But, man, could they say something with a hat!

P.S. Let’s be friends – BEST FRIENDS!

Air kisses and champers to GayProf!

The semiotics of the sartorial are crucial in the iconography of the Star, and yes, honey, Miss Hat can say a whole hell of a lot. Sometimes, a girl needs to make an entrance or exit without a whole lot of words (or alternatively, in a real big hurry, hello!)

By way of explanation on the absence of the hispanoparlante (Spanish-speaking) Divas in my short, short list (for, as any queen can tell you, we could spend all day and twice on Sunday detailing the divas of our lives. Missing but not forgotten: Diana Ross, Grace Jones, Barbara O, Loleatta Holloway, Stephanie Mills, Rosalind Russell, SalSoul Divas, Dorothy Dandridge, Dorian Corey, et al.), I didn't discover the fabulousness of Dolores or Lupe or the other Golden Age stars until grad school, through my girlfriend La Muffin, who was writing his dissertation on them. Like many US Latinos, I grew up primarily anglophone, so my identifications were predicated by language as well as (if not more than) race, which is why the "Blatino" connection is distinct. How do English-speaking Latinos make cultural and social connections which are still grounded by race, but also determined by language? Blatino, baby, you know it!

This has grown and shifted through my love affair with Mr. Gordo, who is South American and has not only reinvigorated my Spanish (ability and confidence: i.e. I can speak Spanish now without feeling my mouth is full of nails) but introduced me to new Divas worthy of any queen's affection. One that comes immediately to mind is La Lupe, the fabulous and tragic Salsa Diva who, in during her horrible life, produced great, cathartic art. In fact, it was amazing to see the universal language of the Queen at play once at a party in Caracas, where one queen in particular had her mimicry of La Lupe down to the hair pins and throwing of shoes. Brilliant! In fact, La Lupe has recently been remixed by the Filter Kingz with her classic single "Se Acabo!/It's Over, Baby!" (available for purchase on Itunes, btw). "...y yo soy La Mala?! Ay!"

Ooh - Downloaded and loving it.

Goddammit! I just lost a long comment about how much I loved this post and how I, too, got started on the road to delicious queer campiness by my mother, who taught me to love, in addition to the divas you mention, Susan Hayward, Gene Tierney, and the slightly-prissy-in-real-life, but still really hot Rosalind Russell (we still over which of us deserves to keep Russell's autobiography Life is a Banquet. Can you believe she wouldn't let me take it when I moved out?)

I'm often described as "really a gay man" because of my love of all things Bette (I have a big, gorgeous blow up of that last picture you posted, of her surrounded by smoke, hanging over my desk--found it at the local gay thriftshop and still can't believe someone gave it up)and while I relish the compliment, I always feel a little stung and ripped off, because I am NOT a gay man, I am a fabuous, bitchy, often vile, gay WOMAN. Where did we go wrong? How did lesbians so totally miss the boat on campiness? Or rather, because I don't think we did miss the boat, how did the stereotypes get so immobile and how did we get stuck with the unfun ones? Was it all that earnest gender-invisibility of the 70s women's movement?

In any case, I take my camp pretty seriously, and am trying hard to instill my queer students with a sense of their cultural heritage because sometimes I get a panicky sense that they just don't get it. All the men who, after my mother, really fostered my love of camp are dead. To this end I teach a course called Deconstructing the Diva (which I developed in now defunct, fabulously old-school queeny bar on Chicago's North side) in which I make them watch movies like The Rose, All About Eve, Mahogony, and The Turning Point, listen to Maria Callas and Dusty Springfield records, and read Trilby, so they'll know a Svengali when they see one. It's all pretty gay 101, but it gives them a place to start and they often come back and report on the delightful divadoms they've started pursuing. So far, they've given me La Lupa (yay!!!!) and Julie London (shrugs shoulders. she's okay, but no Dusty), for example.

Mostly, what I find myself trying to teach in this class is that loving a diva doesn't just effect your life, it MAKES your life, because it gives you an excuse to love BIG and feel passionately about something.

Post a Comment