In the midst of a lingering cold, student appointments, and classroom demands, not to mention trying, unsuccessfully alas, to return to the edits on the manuscript, I ran across an email last week from our Faculty Teaching Centre for a workshop on library resources, which offered a stipend to attend. Given that Miss Oso is broker than our current administration’s policy in Iraq, I signed up, and after some creative rescheduling (i.e. a hasty note on my office door), I was dim-eyed and wet-tailed for the first 9:00 am meeting of the seminar, grasping my coffee as if it were a life line. There were a wide range of faculty there, from many disciplines, and I wondered, as it got under way, how many of us were actually there for the money as opposed to the actual training. My guess would be all of us, in fact. But the stipend aside (which one could argue is perfectly legitimate, since you are taking up faculty time which deserves reimbursement; I wish Sadistic College had offered stipends for all the bullshit one was expected to perform for free), one always learns something useful in these seminars, almost in spite of oneself (and the typically early hour they commence).

Very quickly, we got into a discussion on the role, history, and future of the Library. The session discussants were library science professionals, and wanted to touch on some of the issues in contemporary library culture, then move on to some exercises. However, given that they were speaking to a crowd of faculty, their plan had soon gone awry. The group entered into a lively, if sometimes tense, discussion on the Library and its pasts, presents, and futures, that supplemented the schematic the discussants had proffered, a set of questions not grounded in the research library, per se, but the Library as a social and public institution. What was the function of the library today? What was the mission of the library in a digital age? What were the public perceptions of the library’s past, the realities of the library’s present, and the challenges to its futures?

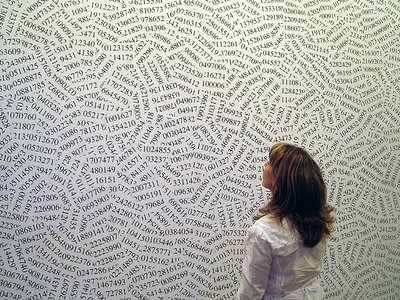

Some of these questions came down to how the library had changed in our collective lifetimes, from quiet places (the infamous and notorious “Shhhhh!”) to increasingly cacophonous spaces of conversation, beeping and ringing cell phones, yakking schoolchildren ("Can't you just shut up and stare into air?"), and interactive activities far outside of the realm of mere books: DVDs, audio materials, classes and courses for the community, and homework centres. One of the discussants made the interesting observation that the political role of the librarian has changed, from guardian of culture to defender of free speech. Perhaps the librarian’s role was always thus, but it struck me as compelling that in the past the librarian was regarded as somewhat of a fuddy-duddy, with rules and the Dewey decimal system and the ever-present shushing, not to mention the long-standing social stereotype of the old maid librarian. Nowadays, libraries, in particular new ones, tend to be bright, social spaces. Librarians come to work in red North Face fleece jackets and techy sneakers, and are constantly cheerfully pimping some event or other: Banned Books Week, Black History Month, Gay Pride Month, Graphic Novels Week, etc. Librarians are now fun! Computers have replaced the card catalogue, and the public has been drawn back into the library as a site of electronic interconnectivity in a manner unknown when I was in high school and college, when the library, in particular the university library, was more of a cloister than community centre.

As part of the seminar, we toured a local public library close to campus, and saw the range of services the “New Library” offered to its patrons: popular DVDs included the notorious Inglés Sin Barreras complete set, a collection of Manga comics, apparently all the rage among the tween set, workout and self-improvement videos. As we looked at the offerings in the homework centre, the discussant, who works with this particular library, told us that they were in the process of purchasing Dance Dance Revolution, which they expected to draw more young people into the library, as well as provide them with more physical exercise (!). This caused firstly a pause, then some serious questions among the group: what exactly did Dance Dance Revolution have to do with the library? Was the library now, in addition to a child- and elder-care centre, now a high school gym (complete with the high school dance)? But it was clear, from the standpoint of any competent understanding of what libraries have had to do to survive, that increasingly libraries have embraced concepts of popular entertainment and child care to fulfill their missions, not to mention to sustain their generally meagre funding. Most of us understood this pressure to compete with other forms of entertainment, and prove one’s social and economic worth to a skeptical and anti-intellectual public through raw numbers of patrons ‘edutained,’ but the inclusion of a crazy televisual dance game with loud music as part of the New Library’s mission struck me as slightly absurd. Have we indeed descended this far? What's next, strippers on Mondays and Bingo on Wednesdays?

Apparently, we have. An interesting part of the introductions was relating a bit of our own history with libraries, in general. Most seminar participants, whether out of a taciturn nature or the early hour, declined to elaborate. But I thought it was actually an excellent question to locate ourselves as intellectuals and educators. Most, if not all, people who hold doctorates in the humanities have spent considerable time in libraries. The dimensions of the time, however, are interesting to parse. For me, at the secondary school level, going to the library was a chore to be done only if impossible to avoid. My high school library was small, certainly not of the Breakfast Club variety, and held very limited resources. Mostly, it was a place for the typical high school pranks, such as pasting maxi-pads on the ends of the shelves or as the milieu for detention for teenage jezebels and delinquents. Like most high school libraries, it was not a place for intellectual repose. I would often have to venture to the local municipal libraries to find material, but made my visits quick jaunts with no lingering. In my youth, libraries were not vibrant places, even if I knew how to use them.

Moving onto Prestigious Eastern U, which offered a range of libraries for every sub-topic and specialty, as well as a large central collection, the relationship shifted. The library now, in that mini-city of eggheads and intellectual discontents, was a social and networking site, as well as a veritable den of inequity. The basement men’s room in the main library was a notorious Tea Room, for the uninitiated a public place where men gathered to have anonymous sex, and even as HIV was on the rise, remained incredibly active. Too shy and virginal to participate or even know about such things, I was schooled by my girlfriend Caribbean Queen, a Haitian-American undergrad who had already lived an infamous sexual life in New York as a teen before coming to study at PU, cruising the public places where men met to have sex. His favourite thing was to sit on a padded bench outside the men’s room and clock the men coming in and out (literally timing their stays, which often lasted for hours) whilst purportedly doing his homework. As well, as we were eventually to learn, he was a participant in the action as well. Since this rest room was right off the general lounge with coffee and snack machines, our group, the Trend Pack, would often gather there with him on his bench to socialise and shoot the shit, no doubt endlessly annoying the cruisers just a few feet away, engaging in the rapid and passing passions of sex in a very old-fashioned men’s room, marble stalls with a large anteroom that had once held furniture but was now barren. So, quickly, I came to associate the university library with sex and socialising, although I’m still not sure of the connection between these two and the millions of books which lay over our heads as we yakked and joked and drank bad coffee and smoked (Yes, Virginia, smoking in the library! Ah, the eighties).

My other favourite library milieu was the Art Library, in a very modern concrete building designed by a once famous but at the time disgraced architect from the sixties (he is back in vogue now). The library, like the building, was once beautiful and compelling but in the eighties was a shambles. Hot in summer and cold in winter, cramped and strangely spaced with occasional leaks necessitating the egregious use of plastic sheeting, it was in spite of its flaws a veritable centre of coolness when I was an undergrad. I even worked there, miserably, my freshman year, after being fired, I mean leaving, my first campus job, as a secretary for two neurotic curators with the same name (the two Janets) at the university gallery. While actually working as a bursary student in the library was anything but glamourous, it did put one at the centre of a certain scene, and gave one a power that was interesting. After all, every cool person had to come to me to check out anything, or get something on reserve. La Zeez, whom I had met my freshman year but did not become friends with until sophomore year, remembers an encounter with me when I worked there, where apparently I was terribly bitchy to her as she checked out material. I had thought her at the time quite the snob, although I don’t remember the incident in detail. Once a Diva, always a Diva, apparently.

In any event, my relationship to the temple of knowledge gained precision in my graduate years, where at a small R1 state school I mastered the modest library fairly quickly, and became proficient with its collections, particularities, and peculiarities, including the strange culture of the university librarian, a creature all its own in the academic ecosphere. After sixteen years of formal schooling, the library finally met its purported mission in my head: as a place for ideas and books and material. On my recent trip back to Doctor Town, Advisor joked that now no one actually goes to the library: it is practically all virtual. The building itself, undergoing a renovation, is planning more shelf space but also more social rooms and spaces, to become more like a community centre rather than an exclusive repository of books. Libraries have of course always had that role and function, but the manner of approaching these aims, especially for public libraries, seems to have entertained a decidedly different scope and scale.

Still, the library in its edutainment mode fulfills vital social functions, as places where children can be relatively safe, where immigrants and pensioners can check out the material that speaks to their needs, where those without home internet access go to check email or buy something online (or look at porn, when they can), therefore lessening the vaunted digital divide. But will the library eventually lose the books and reading and just become a social centre, even on university campuses? This is an interesting question. It is far too easy to err on the side of entertainment rather than education in the synthesis of 'edutainment.' I do think we lose something when the line between the two becomes too blurry. And this is a shame, for the library as a site of self-formation has been central to my own development as an intellectual, albeit in strange and unconventional ways. The New Library does not really appeal to me. If I wanted to spend time with loud schoolchildren and the odd pensioner, I would go to the Mall. Then again, the digital explosion in library resources means that academic misanthropes such as myself no longer have to actually go to a place and see people whilst pursuing books or articles. Remember photocopying? Ha! Some things are indeed not missed. But the new libraries, whatever their paradigmatic limitations, are packed with people. So obviously, a need is being met. But the old library, the shushing and the schoolmarms and the old maids and the cubicles and the card catalogues, gone oh so long ago, will always be central to my understanding of the role and function of the library, even as seemingly this vision withers away or rather transforms itself into another creature entirely.