Well, I’ll need to work a bit on the choreography, but first day classes were suffered through with a modicum of elegance and a minimum of drama. This semester I am teaching two classes on the same day: Intro to My Specialty Studies, and a general education course on American Immigration History. Needless to say, I dazzled the smaller Intro class with my élan, my grace, my charm, my handouts! What can I say, when it’s your specialty, you’ve got materials to the rafters to snow them under in what passes for prep, sort of like an all-you-can-eat Sizzler or Chinese Buffet (don’t lie and say you don’t know the type: they’re all called China Rose or China Flower or something like that, and they all feature the same overly-fried and relatively tasteless food and the same surly waitresses and bored cashiers): quantity in place of quality rules the American brain like Mom, apple pie, and interstates.

In any event, yes, back to the handouts. They were, ahem, suitably impressed. I had actually prepared them last year for some community service event I did for a local K-12 school district, an in-service teacher training, so therefore they were written to be accessible, visually friendly, and relatively comprehensive (I had two hours to communicate a whole mess of stuff to a bunch of teachers who were remarkably like many, although not all, university students: coerced into being there and kept placated by bagels and coffee). Ironically, the suit I wore to class this week was the same I wore last winter to present to the teachers, but instead of shivering (Who needs an overcoat? The door is only twenty metres away. It’s only 20° today!), I was for the first class on the verge of shvitzing, and for the second that verge slipped into a damp and slightly embarrassing reality. What can I say? Fat guys shvitz!

In any event, perhaps because it is my specialty or because it was the first class of the day or because it was smaller, that first class seemed to flow much better than what was to follow. Standard practice at my institution is to hold a full class session on the first day, only part of which can be consumed with syllabus review, no matter how slowly one reads it or how many languages one asks their students to translate it into right there in class for polyglot diversity. Ergo, the handouts. Blitzed by enough snow white copy paper to kill a small forest of innocent, beautiful trees, I reviewed the material, then offered an online tutorial on how to download most of our reading for this semester (NB: While there are many academics seemingly involved in my area of specialty, there is a complete dearth of decent introductory anthologies to use in places where one book counts, i.e. public universities serving working class students. Such a dearth, in fact, I am considering editing a volume myself! This PDF shit is for the birds! I guess it beats actually photocopying. Remember readers? Remember Kinko’s Professor Publishing? Ah, the innocence of the 1980s!)

Two gay students stood out amongst the crowd as possibly interesting, talkative, perky and alert and very “now” gay (e.g. moderately metrosexual, except a little too put together and a little too toned to be truly str8. Oh, they also were carrying the latest edition of Cold City’s gay rag under their arms, so it wasn’t exactly rocket science. Even I don’t read that trash, so they MUST be gay! I mean, who else would bother, unless you had absolutely nothing else to read?). A few older women, always good for measured conversation and really good questions, a couple of jocks (one was falling asleep, just barely, sort of like his no doubt impending performance), some very put together girls (full-face makeup), a handful of students of colour, both "new" and "old" American— in other words, the usual cohort of students one will find in a Cold City U. classroom. No angry older white dudes though, which was unusual. I was to see them later. There was one angry younger white dude, but I couldn’t tell if he could be slotted into the gay sub-group. It is so hard to tell nowadays!

So, feeling fresh, after the successful and brilliant conclusion of Class #1, I jumped in the car and ran across town to get a video from the public library for the second class (lacking the requisite handouts), grabbed a delicious hamburger, and made it back with some time to spare for Class #2. Larger (because it meets general ed requirements), more ethnically diverse (with the angry older white dudes and J-Lo type Asian girls, vaguely fabulously attitude-nous, standing out in the crowd: a potentially spicy mix), and more cautious, it was also much closer in the classroom with 32 bodies present (i.e. it got hot). But I had at least five returning students (it’s nice to be liked), and syllabus review et al went well. I plop in the video and think, “OK, we’ll watch a little of this, then have a conversation based on the video, right?” Well, we did, kinda sorta, but slow, slow, and not very engaged. So then, I fall into an error I am particularly prone to: I start to pontificate. This, that, and the other, blah blah blah, until their eyes glaze over and I know dinner is ready! Ding! Time to leave.

Now, I think on some level pontification is a natural consequence of the practicum of egg-headetry. I yak, therefore I am. It’s something we learn in high school (Pick me!), reinforced in college (I still cringe remembering the time I mouthed off on Maoism, of which I had no idea, in an art history section and was rewarded with the TA’s gracious and laudatory commentary; after that, yakking in class became like crack, and I was Whitney!), and cemented in the graduate seminar room (at times like a gaggle of Canadian geese, honking and barking and shitting everywhere), along with its flipside: sullen, resentful silence (I guess in this sense we come full circle). Prancilla told me a story of a grad school colleague of hers who once had a, ahem, disagreement with a professor at the commencement of a class, and for the rest of the session she sat silent in the seminar room and stared at the professor, throwing daggers with her eyes while at one point, as Prancilla put it, “she slowly unwrapped and ate her sandwich, never once taking her eyes off the professor.” Ouch!

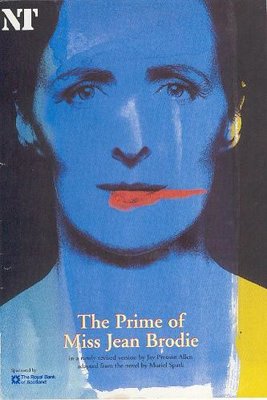

Well, the worst part of the pontificatory moment was the shvitz! So bad I had to start fanning myself with the syllabus. And of course once the schvitz starts, you can’t take off your coat. You have to ride it through, like the soldier you are. It all ended well, mostly, and my pontification tends to be relatively coherent (I try not to veer too far off topic. I'm no Jean Brodie, although I've had my JB moments for sure), earning at least the backhanded compliment of “He’s smart” from students even as they grow bored and restless. Partially, this is due to the fact that the first day one has very little to bounce off of (no reading), to reflect ideas back to students, to foment discussion. Oh, sure, I could have taken out my bags of tricks: groups, free writes, name games, debates, etc. But what would I do later in the semester? But also, larger classes tend to self-regulate their verbal contributions in ways that are hard to see when you are on the stage, and are used to (and perhaps even love) the attention of being the centre of attention, in the luscious limelight. Students, even talkative ones, are cautious as cats, conscious of speaking and what speaking means, the attention it focuses on them, their perception of vulnerability. In the end, they are actually not like us, luminous creatures of the lectern, popping our eyes and offering our overly educated (and most of the time unasked for) opinions about this and that at the drop of a pin. Diálogos impertinentes indeed!

That’s OK, it will get better, but it did leave me feeling a bit deflated. It doesn’t help that Mr. Gordo is at a super-fancy conference in Mexico (loving it, btw, but who wants to talk about the banalities of class when they're in wonderful and horrible Mexico City? Even I'm not that masochistic!), so I have had no one to immediately process all the little fears and paranoia that always plague me on the first day of class (and come to think of it, on many subsequent days of class as well). But thanks to the lovely La Vickstix, Miss Oso has some cash to go get some dinner tonight! I'd love to drown my sorrows, however small they may be, in an In-N-Out burger, but alas, La Vicks didn't send that much money.

In any event, to paraphrase Scarlett O'Hara, there's always next week...