Summer has landed on Cold City with a bang. At least that what it felt like last Sunday, with a luscious high in the 70s and everyone and their grandmother out in the streets and parks and cars, in various states of undress, enjoying the beautiful weather. This would include yours truly, who made his way (late, natch; it was Sunday after all) to a brunch with Prancilla and our girlfriends Sister Disco and Ms. Tee. We found a little place in the middle of a residential neighborhood that was a little bit IKEA, a little bit Wallpaper Magazine, with decent food and a very put upon waitress who looked like she would rather be anywhere than serving up delectable dishes to the sleek-jowled middle-class babbitry and well-groomed gay men kibitzing over eggs, Swedish pancakes, and frittatas.

Revelatory of the way in which the end of the year has warped the lives of four young professors, it took us three weeks of planning and emails to arrange this brunch, although we are all resident in Cold City. I was in charge of picking up Ms. Tee and then meeting Prancilla and Sister Disco at the place, but even after three weeks of email after email I was unclear of the exact time we were meeting, and decided that morning to press the snooze button through several cycles, only to awake to the phone ringing almost simultaneously from three different cell phones in three different locations. What was happening? Where was I? What was the deal? It’s at moments like this that I am thankful for a buzz cut, which significantly reduces one’s primping time post-bath, is generally presentable since there’s really nothing to style, and one never, ever has to deal with bed head. A brief shower (with Klorane Gel douche avec crème nutritive, a souvenir from my last trip to Switzerland), a quick check to see that my zipper was up, and I was flopping out the door in my suede slides to fetch Ms. Tee, Ari Onassis glasses perched on my nose and waltzing into the street with a distinctively sleepy sway. Prancilla and Sister Disco I have known for several years, but I met Ms. Tee at a series of social events for faculty of colour here in Cold City, where she teaches as well, just at another institution. I pulled up to her house, which in fact is only ten blocks from my garret, approximately 20 minutes after getting out of bed, a record even for me and my notorious flojera.

Brunch with friends is always fun, but the feeling Sunday morning seemed extra special, given the weather and the impending close of our labouring duties, all of which gave us a slight buzz, although our summers remain decidedly murky in terms of plans. Over food and blessed coffee, we chatted about our lives, emotional and personal things that needed some group attention. Afterwards, I suggested that we sit outside on the lawn for a bit of sunshine, to which all in attendance rolled their eyes and said, “Oh, you mean to smoke?” which was more or less the truth, so out we went. Our exterior conversation was different in tone from the one in the interior, as we began discussing a series of questions in relation to teaching, in particular the role of hegemony in the responses of students to critical ideas and thinking.

While we all teach at different institutions, and have been trained in different disciplines, we all have certain things in common, not the least of which is that we are faculty of colour in white dominant institutions. But we also share, as many (but not all) faculty of colour do, a commitment to a certain critical approach to society, culture, and politics, which we attempt to instill, in various ways, in our teaching. That said, we all employ different methods in response to this challenge, which could be characterized as both in collaboration and in conflict. We are not pod people after all, and for any given faculty of colour you’ll find a different methodology, including, depressingly, doing nothing at all.

Sister Disco began the conversation by relating a query as to the power of dominant discourses on the student mind, using as an example the reaction of some of her students to Angela Davis’s Are Prisons Obsolete?, which critically takes apart the “Prison-Industrial” complex. The students in Sister Disco’s class could consciously recognize the power and persuasiveness of Davis’s critique, but still presented her with relatively conventional answers to the series of questions Davis presents in her text, namely and to paraphrase, “Prisons are bad, but bad people need to be locked up.” Sister Disco expressed dismay at the inability of critical thinking to penetrate the unconscious mind (and biases) of her students, relating their responses to a script that the students read from, without thinking about it. This engendered a lively conversation about, basically, hegemony and its overwhelming power on our minds, and how this control makes arduous the task of inculcating critical thinking in the classroom. Given that I have had my own series of troubles in my own classes this semester, around assessment, teaching difficult theoretical material in a working class classroom, and maintaining student interest, I found the conversation engaging. It also made me reflect a bit on a teaching conference held at Cold City U, a couple of weeks ago, which also raised several questions in my mind as to what I am trying to do in my classrooms, and how to do that effectively (or at least with less trauma, both for me and my students).

The teaching conference was, in some ways, filled with the usual platitudes we hear nowadays about teaching to the student as an individual, teaching to respect differences, teaching to enable student learning, teaching to reduce trauma and increase retention. And on some level, these teaching conferences always leave me feeling cold (I’ve been to several), the mismatch between educational theory and practice never so wide as in a seminar on teaching. But they are always engaging, if from a position of critique.

What exactly are we doing in the classroom? What are we attempting to achieve with our students? And more largely, what is the function of education in our society? We know the historically traditional approach to education: the model of students as tabulae rasae, to be filled with our collective socio-cultural knowledge. And while this model may have been taken apart by changes in American society stemming from the social movements of the sixties and the turbulence of the years that have followed, many of us, even the most progressive among us, still have at least (perhaps a small) part of one foot in this model. After all, the very structure of the classroom, the hierarchy of the institution, and the social relations that spring from it, are essentially based on this approach. Much discursive hay (and accompanying hand wringing) has been made, however, over the challenges and changes to this model, from both the political Left and Right. In the case of the former, there has been a broad-based movement to make education (and educators, such as we) more responsive to the particular needs of students, the intimacies of differential relationships to education (discrimination, exclusion, institutional and structural neglect), and student “empowerment,” however we want to understand that term (educational success, socio-political enlightenment, “teaching to transgress”). Some ways in which this movement has been influential is firstly in the very fact of teaching conferences for university professionals, in student evaluation forms become an institutional standard, in radical pedagogy methodology being taught unevenly across the institutional spectrum, and a general sense of the need to be present and aware of students as actors and participants in the educational mission.

Alternatively, the Right has a similar interest in student empowerment, in the form of accountability of institutions and educators to providing a commodified educational experience that does not evaluate as much as satisfies consumeristic demand for the quintessential “college experience,” right down to the logos and cute baseball caps. Some of the hallmarks of this particular strain of the movement have been a general turn towards thinking of students as customers and universities and degrees as consumer products, student evaluation forms (natch), online lists of bad radical professors, “Academic Freedom” motions before state legislatures, and a desire to transform academia into a good citizen of the republic of Mammon (the cynics among us would argue it's doing pretty well as it is).

Ironically, the place where these initiatives driven by different political agendas overlap is in the desire to harness the university to the wagon of social change. What both movements have profoundly misrecognized is the deeply conservative nature of the university itself— the Left in its inchoate desire to turn the university into little Radicality factories (“teaching to transgress”), and the Right in misapprehending the already incredibly reactionary nature of the place (graduate student unionization efforts have lately brought this to fore on both sides of the professorial political divide). But more importantly, what is interesting about both post-tradition critiques is that they are still inherently grounded, in some crucial ways, in the tabula rasa model of student consciousness, and do not, moreover cannot, recognize the deeply ambivalent nature of education, both for students and educators.

This ambivalence is found across the educational spectrum. In traditional four-year colleges, students wash up on their shores with the expectation that college is what one does if one is to be successful in our society. Not to sound too Pollyannaish about it, but this is hardly the love of intellectual rigour and practice that we seemingly seek to instill in our students. In non-traditional universities, like Cold City U., you have older students who are more consciously ambitious about the use value of a degree for their actual work lives. But again, this interest is driven not by an interest in intellectualism, per se, but by a utilitarian desire to, in the frankest possible sense, make more money. So students themselves have one idea of what they are in the classroom for, which does not necessarily meet the expectations of the professoriate, at least the humanities version of the professoriate.

But the larger point here is that education is coercion, that most students would rather be working and getting paid for it, or be with their families, or getting high, or eating pizza, or doing laundry, or fucking, or fishing, or whatever it is that undergraduates do, than sitting in a classroom either listening to a deathly dull lecture by an egghead or alternatively running around the classroom doing group exercises and tossing plastic balls and drawing on craft paper. Richard Rodriguez, over twenty years ago, triggered the ire of the Chicano Left for declaring that education was coercion, and declaring simultaneously his ambivalence about it, the necessity of the coercion for the student and society, yet the mourning of the loss of the former self, the burdens of consciousness, the changes to self and family through education. This ambivalence is also deeply grounded in our own experiences as educators, fully aware of the soul-crushing dimensions of our own educational curriculum vitae, as well as the new heights that our intellectualism has brought us.

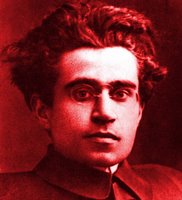

The challenge isn’t ridding education of its coercive aspect, which is the conceit of both the Right and Left in our current educational dramas, but utilizing it to effect some change, however small, in the intellectual lives of our students. And I think this is where most of us are, in reality, conscious of the limitations of our powers as Wizards of Oz yet desirous of doing something, even little things, that are material and lasting. Education as a process is in general a mysterious and non-rational practise, another reason as to why it is impossible to harness, really, to any explicit political or social agenda other than hegemony, which is implicitly woven throughout our practices, be they radical or reactionary. But the misapprehension of hegemony is that it is static, unmoving, immobile. Close readers of Gramsci will recognize, however, that hegemony is fluid, transforming, shape shifting. So, to put it colloquially, every little bit counts, to shift and mould hegemony. Which is why the purported leftist bias of the professoriate is so threatening to the political Right, because they, on some pre-Lapsarian unconscious level, recognize this elemental fact of hegemony, and wish to control it.

I teach in a field that has a contemporary history of using the classroom for radical ends, teaching students to transgress, attempting to ideological patrol the waters of the student mind, and turning students into soldiers for radical critique and change. While perhaps a laudable goal at one point, this model failed (and continues to fail) to take into account that, indeed following contemporary pedagogical theory, students are actors. All of which is to say that they are not vessels to be filled with our knowledge, but intellectual personae that need, on some essential level, to be persuaded, enticed, and seduced to accepting and employing our models of thinking.

Sometimes this is a complicated dance. While I teach hot button topics, I attempt in my classrooms to have an ideologically flat experience, to appeal to historical and political fact to convince rather than exhortation and haranguing. However, I have felt several times this semester that I crossed a line sometimes, revealed too much of my own political agenda, in an attempt to get students to engage with ideas and topics, triggering fears that my name will end up on some list of radical professors seeking to damage their students with their political views. The years during which I received my graduate education were ideologically polarized ones, and during my teacher training it was easy to spark conversation (sometimes to disastrous effect) by touching on racial, sexual, gendered controversy. Ten years later and in a different geographic and ideological world, it is less easy. The bored faces I have confronted this semester, disinterested in the reading and even less interested in conversation, have been a peculiar challenge. It is of course class and semester specific, for teaching the same material last year was easier.

My goals as an instructor strike me as fairly modest. I don’t necessarily “teach to transgress.” This particular articulation has always struck me as particularly self-indulgent, for it seems to exalt the ideological goodness of the professor/educator and seemingly only serves as political self-aggrandizement, since most “activist-educators” I know are teaching at R1 universities and making a whole lot more money than I am, with a whole lot less teaching. Yet, I do seek to affect some sort of intellectual process among my students, obviously. To find a position in relation to the material and critiques presented within. To take an articulated stand, whether in opposition or agreement, and be able to defend, rationalize it, define its borders and content with some coherency. In my mind, it is fine if my students leave my class as conservative or centrist as they entered, as long as they own it. This returns us to Sister Disco’s exasperation with her students: they refused to own their complicity. No one is perfect, least of all professors, but owning up to one’s choices (political, social, economic, or otherwise) is a good step in the right direction of any pedagogy.

But students, reflecting the society they live in, steadfastly resist this intellectual move. Students, like our society, want a beautiful experience, without the messiness and complications that human life entails. And this suits ideology just fine, as it prefers to remain invisible, unconscious, behind the scenes. I suppose in this sense students cannot be blamed for this laziness, given that we inhabit a resentful and schizophrenic society with free lunch for some and punition for most, but at the same time students cannot be excused from their responsibility as actors in their own lives. This is painful for them, and often times for the instructor as well. This is the pain of education that Rodriguez so eloquently tried to capture: the pain of educational consciousness.

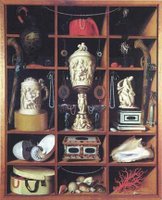

A Wunderkammer is a “chamber of wonders,” a cabinet of curiosities, a nice little term I learned while viewing the work of Kiki Smith once in New York, who has a work with the same title. And it struck me as apropos to our modest and strange tools that we use as educators to reveal the superstructure of ideologies that rule our lives. In general, the contemporary classroom is no longer simply books and lectures, at least for most of us. Often we use textually based sources, history or narrative or primary documents. Other times personal stories in the classroom, the sharing of experiences. Yet other times videos and media-evidence to show students the larger world around them. Sometimes it the force of professorial exhortation or exasperation, as I have had to do this semester, which always risks the conscious rejection of students. In my case in particular, because of the area I teach in, I feel my own Wunderkammer must be stocked with a great many things, as I am attempting, both in the subject matter as well as in my methodology, to displace a vast amount of commonsense knowledge, not to transform my students into ideological soldiers but to get them to find ownership in their lives and in their society.

In this sense, our Wunderkammer are also magical and alchemic, we educators like witches over a cauldron, a little toadstool here, puppy’s tail there, pop rocks and Bionic Woman lunch boxes and bell hooks and Stuart Hall and Paolo Freire and Mom and the Dean and student evaluations and our mentor and our advisor and our committee and our first grade teacher and our favourite teacher and our pencils and our pens and our Trapper Keepers and our most hated teacher and our most boring lectures and our exhilaration and our best class and our worst class and ourselves, constantly changing our recipe to bewitch our students, to entice, to persuade, to communicate, in short, to educate.

Sometimes, however, the burlesque of our curious objects seems like an almost desperate attempt to engage our students in the realm of ideas. At the end of the semester, of course, this bump and grind has ground its last hip sway, as the professoriate collapses from exhaustion. Did it work? Did they learn? Were we effective? These are questions we shall ask ourselves, after the dust of the semester settles, and continue to ask ourselves as we teach. And they oft repeated truism of the student, twenty years later, who remembers us or a moment in the classroom that transformed their lives, probably remains the best that most of us can hope for, since education rarely offers us immediate effects, instant gratification, overnight results.

Yet, this is what university education seems to be up against, and increasingly capitulating to: instant gratification. You see it in surly students with credit-card attitudes and mealy-mouthed administrators smoothing over ruffled feathers. You also see it in the classroom, as professors, even in tenure-line positions, play up to students and grade high, to ensure good evaluations and glowing comments on RateMyProfessor.com. While our intellectual practice is archaic and quaint in many of its values, the brutalism of either Mammon or Stalin, broadly put, strikes me as an even more unpleasant venture. I do wonder, however, how long we shall be able to hold onto our values and approaches, our peculiar Wunderkammer, as the institution, like our society, changes and shifts and transforms, as both the Left and Right march forward with demands for empirical evidence, facts on paper. Yet, teaching remains intangible, mysterious, complicated, compromised.

All the teaching seminars and pedagogical yak and legislature bills and student attitudes won’t change this fact, but do risk driving it underground, deforming it, destroying its open practice. And that would be a terrible thing, both for our students, our society, and ourselves, as curators of the curious object of education, the chamber of wonders, in a world that thinks it no longer needs the peculiarity of that particular form of education.