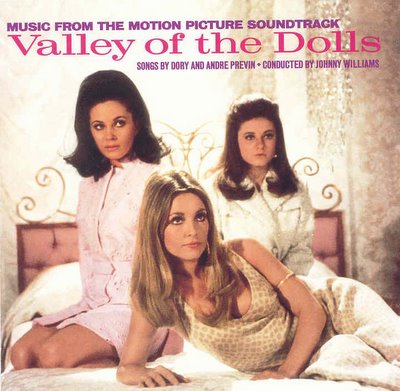

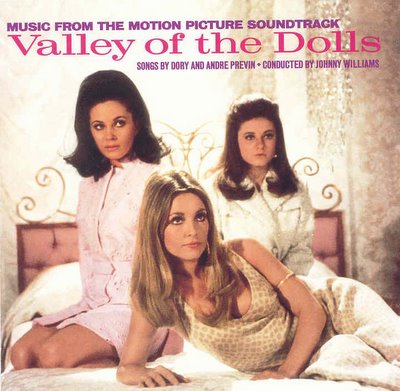

You’ve got to climb Mount Everest to reach The Valley of the Dolls. It’s a brutal climb to reach that peak. You stand there waiting for the rush of exhilaration. But it doesn’t come. You’re alone and the feeling of loneliness is overpowering.

You’ve got to climb Mount Everest to reach The Valley of the Dolls. It’s a brutal climb to reach that peak. You stand there waiting for the rush of exhilaration. But it doesn’t come. You’re alone and the feeling of loneliness is overpowering.

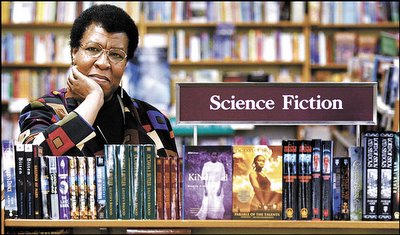

— Jacqueline Susann¡Meet the Search Committee! The dark heart of the academic search machine lies in the committee, and the political and institutional intrigues that surround it. All committees are political, as are all searches, in one way or another. But in this sense, not all searches are created equally. Some are overly burdened by the freight of differing institutional histories and traumas (usually revealed coyly at some point in the campus visit); some are a cover story, with the candidate of choice just off-stage, waiting to assume his or her preordained position after a whole lot of wasted paper, letters, and campus visits (the Ivies and increasingly wannabe Ivies are famous for this little gesture: Ever see an advert for a job at Harvard in English, specialty open? There you have it!); yet others represent struggles over the heart and soul of departments in crisis, for which there will be no happy ending (typically revealing themselves in widely disparate qualifications: 18th Century Lit and/or Woman of Color Feminisms in the same position listing, for instance).

Like Susann's fabulous vixens, eyes firmly focused on success, getting to the Valley of the Dolls, in our case the tenure-track, is a struggle, but once you're there, you confront a whole new set of challenges. Being on a search committee counts towards one's requirements for university service, and it is not for nothing that often a search committee placement ranks much higher in this pecking order than, say, the library committee. Search committees are, in a word, contained hysteria masquerading as process and procedure. They are the raw, unsettled core of the institution and its values that can provide, to the junior faculty member conscious enough to learn its lessons, a sentimental education worth its weight in gold (if not in time and energy spent). And as Susann ripped the wig off of the facade of Hollywood and Broadway, isn't it time someone ripped the wig off the purportedly meritocratic process of selecting the "best" candidate? Girls, let's roll...

This year I have had the unfortunate privilege of being on several committees, not necessarily by design but by necessity. Suffice it to say that I have learned an awful lot about the way the institution runs, its histories and disagreements, and exactly how candidates are chosen. It isn't pretty. Now, as I've said before, this sudden switch from eager-beaver candidate to committee member making and breaking candidates has been one of the more intense aspects of the process for me. In fact, junior faculty never lead committees, but rather mostly follow: that is, divine clues and hints from those institutional players who are setting the agenda (the committee chair, other tenured members of your department, crucial key campus allies on the committee, your Dean). So, the latitude given junior committee members is fairly discrete. Sometimes it gets to the point where you have to wonder what you're doing on the committee at all. Why couldn't they have hashed it out without you, because Goddess knows as a junior faculty member you have better things to be doing!

"I have to get up at five o'clock in the morning and SPARKLE, Neely, SPARKLE!"But here is the delicate and complicated art of committee staffing. Like defusing a nuclear warhead, only not as fun, who composes the committee is usually an art unto itself. The

symbolic logic of placement is important. You must have:

a) key allies, who will work in your (the department, the college, you personally) interests.

b) You must balance off (if you are strategic) with key opponents, who will feel like they are a part of the decision making process, but in the end (and ideally) will be compromised by the very process they seek to influence (see key allies).

c) In many institutions you must have a "community" member (student, staff, or alumni), who will be so clueless as to let you have your way (unless they are serving as currency for outside detractors, stakeholders, or internal sociopaths/critics).

Mix it all in a leaky boat of non-confidential confidentiality and unstable academic personalities and desires and you have the search committee. Ah, alchemy!

"Gimme a Doll, Just ONE doll!" Now, mind you, this is an ideal situation. Different institutions have different rules that guide committee formation. Usually the chair and the Dean hash it out, but often, especially in controversial searches, it can be quite hard to adequately staff the committee, not only given the time investment, but also by refusing to participate, different stakeholders can seek to malign the process and tank the search (in the beginning by refusing to participate or at the end by claiming they weren't invited to participate). In really bad cases various provosts, other deans, EEOC personnel, and even presidents can poke their noses around, causing even more headaches.

And this is all before the announcement for the position is even released. See? UGLY!

This politicking goes on for the length and breadth of a search, which remember is longer for the committee than it is for any individual erstwhile candidate. The important parameters for any search are stakeholders and politics. Stakeholders include anybody with an interest, or more to the point, a beef with the position, department, or persons therein. And usually, these beefs are personal. In fact, most of the politics involved are personal, and by personal I mean exactly that. Professor So-and-So hates Dean What's-His-Name ("He never says hello in the hallway!"; "He leaves the seat up in the unisex bathroom!"; "He slept/stole/married my wife/husband/girlfriend/boyfriend!"), and now is gonna fuck his shit up by being on that committee. That sort of stuff.

"Neely, you know how bitchy fags can be..."Politics can be even more intense when they involve generational or paradigmatic differences which, in the quotidian world, amount to little more than a hill of beans, but in the hyperinflated hothouse of academic egomania, mean everything and more. Not many people can find that they can give a shit about whether the New Deconstructionists or the old New Critics are in charge of the English Department at So-So U, but because so many of our senior colleagues don't have lives, it really is all they have going. And because so many of our senior colleagues are in so many ways less qualified than their present and future junior colleagues (even after 20 or 30 years in the profession), the stakes are even higher. Ever wonder why Job X went to the numbnut you went to grad school with? Well, there's your answer in a nutshell.

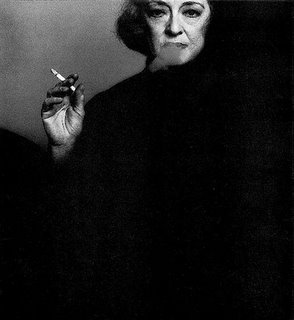

"The only hit that comes out of a Helen Lawson show is Helen Lawson, and that's ME, baby, remember?" It's all they have left, since many of them have either no book or one book to show for thirty years on the institutional teat. Deadwood lives, and it does not like competition!

When I said before that it really isn't about you, the candidate, I really meant it. Sure, individual performance counts. One CAN tank their interview, it happens all the time (unprepared, ungroomed, unprofessional, uninterested).

"They drummed you out of Hollywood, so you come crawling back to Broadway. But Broadway doesn't go for booze and dope. Now get out of my way, I've got a man waiting for me." But committees make decisions, the important decisions (i.e. who to hire) based on all sorts of criteria totally separate from the candidates themselves (at least their professional presentation). Does the job "belong" to a certain field or community? Who does the committee have to satisfy? Is there a racial or sexual inflection (i.e. do we need to hire a person of color, or alternatively, and perhaps more frequently, can we make a show of hiring a candidate of color and then just go ahead and hire the white candidate we feel most comfortable with anyhow?)? Is there an inside candidate or favoured applicant who will be bounced forward (i.e. nepotism)? By the time a short list has been arrived at, most likely all the candidates would do fine. It is time for the nit-picking and hob-knobbing and under-the-table politicking, and pressure exerted on Deans, community members, and members of the committee itself at this point that makes or breaks a case. All of which is all about the specific institutional location and history, and has nothing whatsoever to do with the candidates.

Some examples, not my own: Once, a colleague on a search committee at an old institution told me that one of the senior faculty members was basically tanking all the dossiers from women of color candidates, specifically because the two or three (!) previous occupants of the line had been women of color, and she didn't want any more "unpleasantness" in that regard. So, for a position in minority literature, the committee in essence could not consider any applicant from a (known or self-identified) woman of color. In another case, again at an old institution, a candidate was eliminated from the running because, to paraphrase their detractors, "We don't want or need a black person who talks about Kant." Succinctly put! Committees and the institutions that support them never really want a candidate who will truly challenge them or change their thinking. Remember, the university is one of the most conservative institutions in our society. Or I could tell you the story of my girl F., who is so fierce that to get rid of her the search committee had to change the qualifications for the job in mid-campus visit! Which, to my mind, only speaks to her innate fierceness, when a committee has to go to such extraordinary lengths to make sure it hires "appropriate" candidates of color (i.e. flawless but witless tokens).

"Neely, you know it's bad to take liquor with those pills."In terms of my own experience this year, let's just say I was surprised at the level of interference from outside stakeholders, along with the constant second-guessing on the part of some in the university community as to the intentions of the search committees. Who we eventually hired was truly dependent on agendas I would argue were not in the best interest of the department, which may represent a failure of the chair to exert appropriate leadership but rather speaks more to the dogmatic and exhausting nature of controversial searches: by the end you just want it over, and you don't care if they sign Mickey Mouse as long as it will shut your detractors up.

"Come live with me, and BE my love..."Then again, the perspective of being ON a committee rather than performing FOR a committee has been compelling. What I think has been most interesting for me this year has been the palpable pecking order present among our candidates, and their unrealistic and puffed-up expectations of where they see themselves, which I found thoroughly unpleasant to watch. Now, girls, this isn't my first time at the Rodeo, and I've seen 'em high and I've seen 'em low. My previous post at Sadistic College was pretigious, but hell on wheels. Fit is real, and finding the right fit may indeed not be at a top ten public university or pretigious private one. You can land at Nothing-Special U and end up loving it. After all, we're all not destined for Yale, not that some of us would even want to work there. The Gold Standard for grad students is Research One (PhD granting) institutions, with time and money, but also with such intense politics that one truly must be a barracuda to survive. Some of our candidates were clearly uninterested in working at a non-Research One institution, yet with this attitude are potentially shutting themselves out of a potentially lucrative market: isn't it sometimes better to be a big fish in a small pond, and be

appreciated, than a small fish in a sea of pirannas? So candidates too exert agency on a committee, especially when an underfunded institution wants to nab a half-way decent candidate who may have other options (see trendy, below).

"Mother, I know I don't have any talent, and I know I all I have is a body, and I am doing my bust exercise."To wit, more than a handful of the finalists high-hatted us, either at the offer stage or during the actual campus visit, with clear signs they weren't terribly interested, or demanding incredible starting salaries as ABDs with no experience. Talk about chutzpah!

"They love Helen Lawson and they love Neely O'Hara!" You have to wonder who is advising these people. But also, you have to wonder about how candidates see themselves in the profession. Do these people read the

Chronicle of Higher Education? Do they read

Academe? Do they keep up with developments in the job crisis that is now 30 years old? Do they realize that we all can't live in California, much less with a California salary?

But here again is another interesting and disgusting differential that plays into committees and their candidate selection:

being well-networked. Remember all the ass-kissing you never did in grad school? Well, you better, because it means you run less of a chance at a prestigious post. Remember all your horrible grad student colleagues who were, let's face it, stupid, but certainly had a way with brown-nosing? Well, those people end up with fellowships and good jobs. The "Cultural Studies" shelves in bookstores are weighted down with their dreck. The book "everybody" is reading and better yet, citing, turns out to be completely vacuous! You know, because you, unlike others, have actually read the book. You, sage scholar, are lucky if you end up with a job at all. Think of it like the high-school cafeteria: who are the cool kids, and who do they hang out with? This is academia. Everyone wants to be a cool kid, and nobody likes the nerds.

All of which is to say that the particular sociopathology of the search committee is one which is reflective of the profession, from grad school to emeritus, from job searching to committee selecting, from department politics to who gets tenure and fellowships. Lemming-like, academics follow trends and styles (disciplinary or otherwise), and seek to be as good as if not better than their professional Joneses. This is why certain candidates come away with their pick of the litter while many, many others never land a tenure-track job. In fact, the academy is so trendy it should have its own

People Magazine. The demise of

Lingua Franca is still mourned by those of us who remember it in its heyday, as exactly the

People Magazine of the Egg Head Set.

In conclusion, some dictums on the behaviour of search committees could prove useful as a corollary to the dictums for candidates, if only to serve as a warning to fellow travelers:

1) Search Committees represent the sociopathology of the institution and the profession: nepotism, racism, sexism, personal and institutional insecurities, fear of competition, homophobia.

2) Search Committees and their selections are always political, rarely if ever meritocratic.

3) You don't still believe in meritocracy, do you?

4) Search Committes rarely are acutely conscious of their actions, even after a hire is made.

5) Search Committees are influenced by things like trends, networks, and pressure.

6) Search Committees are hellish to serve on. (see #7)

7) Search Committees are a thankless task. (see #6)

8) Everyone active in the profession will eventually serve and suffer on a search committee. (see #6 and #7)

9) All candidates circulate as currency; knowing and using this improves your chances of selection. (see #1, #2, and #5)

10) Search Committees are irrational organic states of being.

I hope this helps clarify some issues. But don't worry, there's always next year! And girls, don't forget your beautiful, beautiful DOLLS! You'll need them...

Gotta get off, gonna get

Have to get off from this ride

Gotta get hold, gonna get

Need to get hold of my pride

When did I get, where did I

How was I caught in this game

When will I know, where will I

How will I think of my name

When did I stop feeling sure, feeling safe

And start wondering why, wondering why-Theme from the Valley of the Dolls